Tips for Noise Reduction in a Home Studio

Article Content

One of the challenges of working in a home-based project studio is dealing with noise. The sources and types of noise are numerous, but there are methods to help reduce these sorts of problems, many of which are relatively low cost or free.

Types of Noise

Cirrus Research is a UK company specializing in noise — not making it but measuring, controlling and reducing it. The company is focused more on industrial applications rather than musical, but they offer a useful way to categorize pretty much any noise you might come across into four basic types:

- Continuous noise – noise that is produced continuously, usually at a consistent level

- Intermittent noise – intermittent noise is a noise level that increases and decreases rapidly

- Impulsive noise – sudden bursts of noise

- Low-frequency noise – rumble

This is a nice way to consider noise — based on duration and frequency range — since this can help determine the best mitigation method. Any noise you encounter in audio production will easily fall into one or more of these categories.

Types of Noise in Audio Production

- Wind noise – an issue in field recording that usually takes the form of low-frequency thumps and rumble, often resulting in dropouts

- Hum – a buzzing sound typically related to the electrical system (50 Hz or 60 Hz) or ground problems

- Buzz – related to hum and occurring at the same frequency and upper harmonics

- RF interference – caused by radio frequencies or wireless signals

- Electrical noise – caused by ground loops, improper studio lighting, bad cables & connections or improper cable positioning

- Environmental noise – external noise like traffic, neighbors, animals, etc.

- Mechanical noise – HVAC systems or cooling fans for computers and gear

- Sibilance and plosives – noise related to vocal production

- Hiss – high frequency noise often related to the self-noise generated by instruments, amplifiers, microphones, etc.

- Crackle and clicks – intermittent transient noise often caused by bad cabling or connections, dirty potentiometers & sliders or sample rate inconsistencies.

Anti-Noise Precautions in Production

Wind Protection

When field recording, in film production work especially, wind and environmental issues necessitate the need for some sort of wind protection. Two common devices used typically with shotgun microphones are the fuzzy (which fits right over the mic and is otherwise known as a windscreen), and the fuzzy-covered zeppelin, in which the mic is suspended. For more on field recording in general, check my article:

A Guide to Field Recording: Location, Hardware, Software & More

Other than that, it is a good idea to use a high-pass filter (around 80 Hz or higher, depending on what you are recording) to reduce rumble caused by wind. It is really difficult to successfully and transparently correct a recording badly impaired by wind problems, so it is essential to deal with the issue at the source.

Cables and Positioning

Electrical noise caused by bad cables or unbalanced cables can be vexing. All cables will eventually go bad with constant use. Normally the problem will occur at the cable end and knowing how to properly solder can save time and money. While balanced cables are designed to eliminate external noise from entering the signal, unbalanced cables are vulnerable to all sorts of noise such as interference from radio frequencies & other wireless signals, computer screens and AC power lines.

- If unbalanced cables are necessary, such as for guitars and some synths, care should be taken to keep lengths relatively short (less than 10 feet).

- For longer runs, use a direct box to convert unbalanced signals to balanced signals.

- Keep cable runs organized – avoid bird nest tangles.

- Avoid running cables parallel to AC lines, near computer screens or near other electromagnetic devices.

Unbalanced cable

Balanced cables

Electrical Noise and Ground Loops

Ground loops and electrical noise can be maddening problems. They are caused by variations in circuit design between various devices and inconsistent voltages across different pieces of gear. These take the form of hum and buzz in the signal. Aside from the cabling issues mentioned above, a few other simple precautions can help:

- Use the same electrical circuit for all gear being used.

- Make especially sure that tube mic power supplies and preamps are connected to the same electrical circuit. When this is not possible, use a line-level isolation transformer to reduce hum.

-

Keep other devices not part of the signal chain separated, like air conditioning units and lighting.

- Many direct boxes and re-amp boxes have ground lift switches that can be activated to isolate the ground and reduce hum.

- Use a power conditioning unit for all music gear. These devices are designed to regulate the voltage to avoid surges and sags, and help to keep lines quiet.

- Avoid the use of lighting faders and fluorescent lights at all costs (LEDs are a good option).

- Use nylon washers when installing rack gear to prevent ground loops caused by the rails.

- Clean or service potentiometers and sliders on gear to remove built-up dust and debris.

(Huber 422)

Line-level isolation transformer

Power conditioner

Direct box with ground lift switch

Finding the source of a ground loop can sometimes be accomplished by unplugging everything in the signal chain and then adding things back in one by one until the noise reappears. Once you’ve found the offending piece of gear you can take steps to mitigate the issue using the steps outlined above.

WARNING: lifting the ground on a device can increase the danger of electrical shock and should not be done using the common three-prong to two-prong adaptor. Ungrounded equipment can cause death! British musicians Leslie Harvey and Keith Relf were, in the 1970s, examples of this type of electrocution, in both cases fatal. (Source)

DO NOT USE

Improper Gain Staging

Bad recording levels or improper gain staging can inject noise into an otherwise healthy signal path. Every piece of gear or software will affect the gain of a signal. Weak or overdriven signals once recorded can not always be returned to healthy levels without adding noise and other audio artifacts. For a good discussion on gain staging check out these other resources at the Pro Audio Files:

- 4 Tips for Perfect Digital Gain Staging

- Gain Staging: What to Know, and Why You Shouldn’t Stress out About It

Environmental Noise

So what can you do if you don’t have the funds to create a perfectly isolated recording space? Noise from traffic, barking dogs, neighbors and birds can ruin an otherwise great take. Aside from adding acoustic treatment to windows and doors, one simple solution is to schedule your recordings at the quietest times – usually at night or, depending on your neighborhood, late morning might be good when everyone else is slaving away at their regular jobs. Birds usually don’t chirp at night and traffic is at a minimum. If you can’t keep the environment out, the only option is to work with it on its own terms.

Mechanical Noise

Noise generated by AC and heating systems can ruin a recording. Other than revamping the whole system to be acoustically friendly, the only other option is to simply turn those systems off when recording. Being actively aware of the issue is crucial because we tend to naturally ignore this type of low-level background noise. But when listening to the recording it becomes obvious and irritating.

Cooling fans from computer equipment are another source of mechanical noise. These can sometimes be manually and temporarily disabled (at the risk of overheating the equipment of course). Other than that, find a way to isolate the noise in another room, or using isolation box is an alternative option.

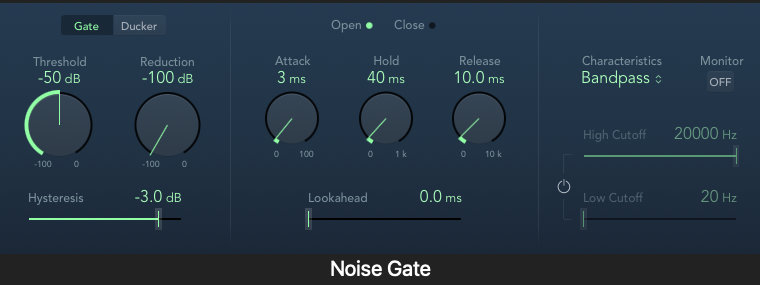

Instrument and Amplifier Generated Noise

Amplifiers and single-coil guitar pickups are notorious noise producers. A common noise elimination strategy is the use of noise gates (hardware or software-based). These take user-defined low level signals and drop them down to negative infinity. But the defined noise in the system still exists when the overall level is above the threshold. The gate attack time determines how fast the gate returns as the level begins to drop. This can create some unintended weirdness, as a sustained chord fades away for instance, so parameters need to be tweaked on a case-by-case basis. An expander is similar to a gate with more control over the reduced signal level. They expand the dynamic range, in a process antithetical to audio compression. EQ can sometimes isolate and remove noise but should be used with caution since this is an indiscriminate filtering method that can remove parts of the desired signal as well.

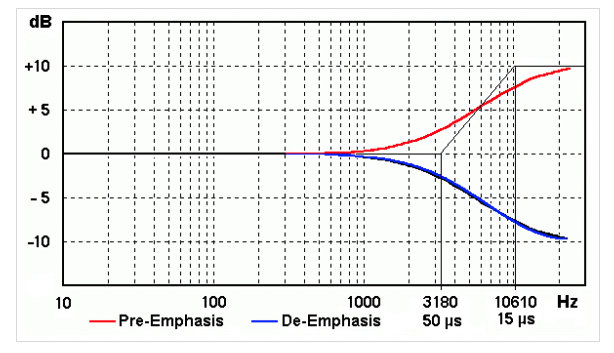

Pre-emphasis and de-emphasis was a technique used when recording to tape was the main technology. In this method of noise reduction, a high-frequency shelving filter boosted the upper frequencies during recording, after which a similar shelving filter attenuated the signal at the same cutoff frequency to bring the signal back to a normal level while reducing any hiss instigated during recording to a lower level. (Rumsey 190)

Pre-emphasis and de-emphasis filters (source)

This is an interesting trick that has other creative implications as well. As Cristofer Odqvist points out in his excellent book, Making Sound, the same idea can be used experimentally to instigate timbral changes not otherwise possible (Odqvist 18).

Vocal Related Noise

Vocal noise is instigated by the performer through the natural act of speaking or singing. Language is full of transient sounds that can be problematic when you try recording them. The two most common means of reducing these types of noises in production are the use of pop filters and simple mic positioning (to mitigate plosive sounds). Other noise-based issues like sibilance are better handled by software solutions mentioned below.

Pop filter

Noise Reduction in Post Production — Software Solutions

If you are given or have created files with noise issues there is still hope. In fact, one of the primary duties in post-production is noise reduction and there are several excellent tools at your disposal. As mentioned earlier, gates and expanders can help to reduce noise. These are fairly aggressive solutions but can be appropriate for certain circumstances. Below are the two native Logic Pro plugins.

Notch EQ can be an effective solution for frequency-specific noises. FabFilter Pro-Q 3 offers an excellent surgical setting with an ultra-steep slope for this purpose.

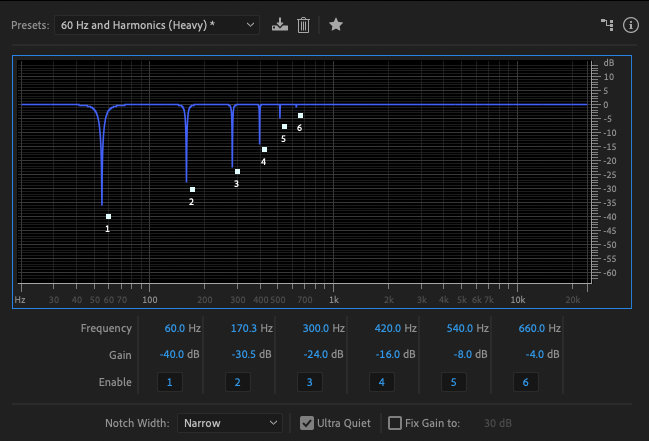

Some EQs have settings that instigate notches at a fundamental frequency and harmonically related frequencies above – great for reducing buzzing effects.

60 cycle hum suppression

De-Essers are frequency-specific compressors that reduce the level of frequencies where sibilance typically occurs (5 kHz -10 kHz). Because they are adaptive and dynamic processors, they only work when an offending transient occurs. So the signal remains basically intact while only the noisy peaks are tamed.

FabFilter’s Pro-DS plugin

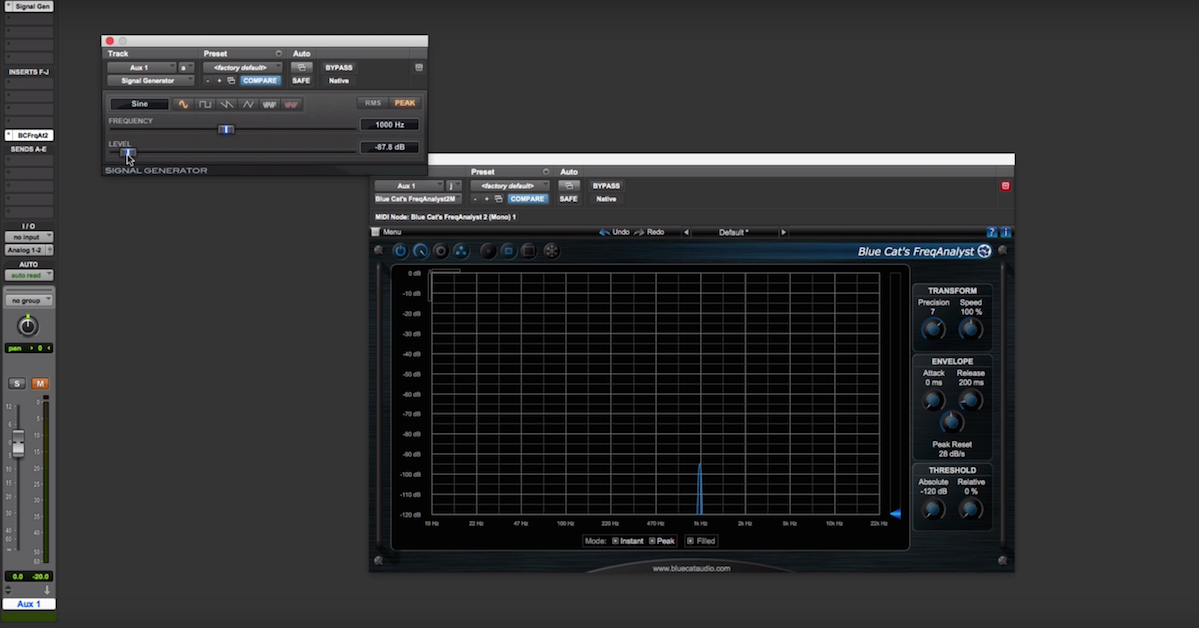

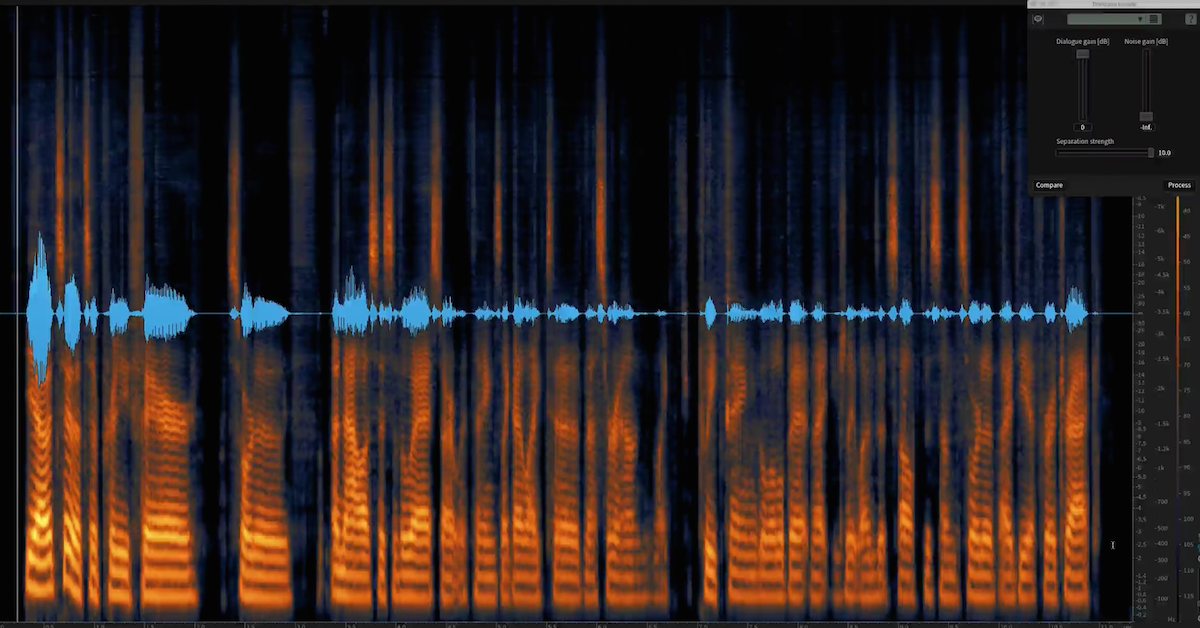

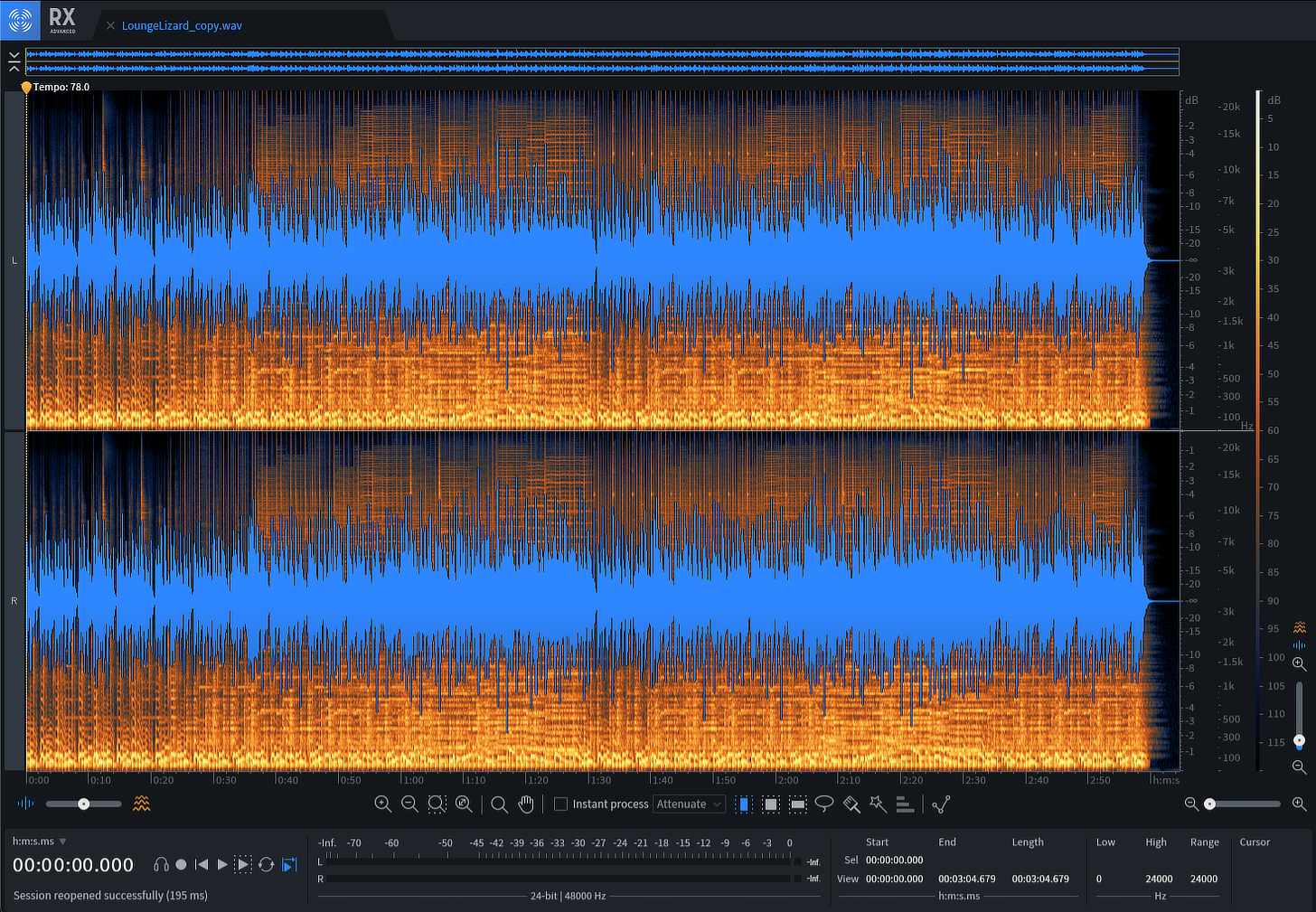

The go-to method for reducing noise in post for many engineers is digital noise reduction software that uses a process known as FFT (fast Fourier transform). This algorithm analyzes a complex form so that it can be expressed as a collection of sine waves, creating a table of data that includes frequency, amplitude and phase. Once the noise is identified by the user, usually by selecting a little slice of audio that has only noise in it, the algorithm can go about looking for other similar sounds in the file and reduce the level as needed. This differs from other methods because it attempts to retain desired audio that occurs even at the same instance. Some of these applications offer dynamic noise reduction processing that reacts to the noise level at any given time based on the content to reduce artifacts. The software has gotten better and faster over the years and the company that has really set the bar high in this area is iZotope with the RX9 Suite.

The RX9 Suite offers noise-specific reduction processes such as: De-bleed, De-click, De-clip, De-crackle, De-ess, De-hum, De-plosive, De-rustle, De-wind, Voice De-noise and more. It’s an exhaustive collection that is a must-have for anyone in post production for the moving image but is also highly useful for music production as well, since it is a great audio editor in general. It’s perfect for tweaking custom samples or cleaning up existing audio recordings.

I recommend checking out Danny Echevarria’s article 6 Plugins for Saving Unusable Audio for some other great software solutions for noise reduction.

Conclusions

Unwanted noise in music has been a source of consternation since recording began and it remains a germane topic even in the age of 24-bit digital audio that boasts a 144 dB signal to noise ratio. We are truly in the golden age of noise reduction in terms of hardware and software, and things will only get better and faster. But this article is structured in a way that suggests it is much better to avoid the noise to begin with – before or during the recording process – than to try and “fix it in the mix.” So take the time to analyze your environment and tweak your studio set-up before you hit that record button. You’ll thank me later.

References

Bartlett, Bruce, and Jenny Bartlett. Practical Recording Techniques: The Step-by-Step Approach to Professional Audio Recording. Routeledge, 2017.

Huber, David Miles, and Robert E. Runstein. Modern Recording Techniques. Routledge, 2018.

Odqvist, Cristofer. Making Sound. Cristofer Odqvist, 2019.

Rumsey, Francis. Sound and Recording. Routledge, 2021.

Thompson, Daniel M. Understanding Audio: Getting the Most out of Your Project or Professional Recording Studio. Berklee Press, 2018.

Winer, Ethan. The Audio Expert: Everything You Need to Know about Audio. Routledge, 2018.

Check out my other articles, reviews and interviews

Follow me on Twitter / Instagram / YouTube