4 Recording and Mixing Lessons from Vintage Jazz Records

Article Content

There’s something about vintage jazz recordings that creates a listening experience like no other. Dim the lights, pour yourself a nice drink, and put some Bill Evans on the turntable and you’ve got instant class, my friend.

Many of the jazz recordings made in the ‘50s and ‘60s might be labeled as “bad” recordings by today’s standards, but the fact that a bunch of songs recorded half a century ago can still have a major impact on listeners today is a major testament to the artists, producers and engineers who brought this music to life. Despite the technological limitations of the day, these artists produced some of the most enduring music of all time. In fact, it was because of some of these limitations that this music is so interesting to listen to.

Modern recording and mixing techniques may have changed a lot since the glory days of jazz, but there’s still a lot we can learn from listening to these old-school recordings. Here are some lessons from vintage jazz recordings that we can apply to modern-day music making.

1. Mic Choice as EQ

The liner notes to John Coltrane’s 1960 album “Giant Steps” on Atlantic records state: “Atlantic uses Electro-Voice 667, Capps and Telefunken U-47 microphones and Ampex Model 300-8R tape recorder for its recording sessions.” They also tell us that “Individual microphone equalization” during the session was “not permitted.”

We can’t travel back in time to see exactly how engineers Tom Dowd and Phil Iehle set up the microphones for this session, but this description gives us a good idea of how things worked in 1960.

The liner notes on this album go on to say that “The sound created by the musicians and singers is reproduced as faithfully as possible, and special care is taken to preserve the frequency range as well as the dynamic range of each performance,” and clearly those particular microphones were chosen with this idea in mind.

These days, we’re often quick to pull up an EQ plugin when we could get closer to the sound we want simply by choosing the right microphone. Of course we don’t all have U47s in the studio, but even making the switch from a large diaphragm to a small diaphragm condenser, or a condenser to a ribbon can have a major effect on the sound we capture.

2. LCR Panning

At the time when many classic jazz albums were recorded, stereo recording and playback were in the early phases of development. This meant that the panning options on the mixing console, if any, were limited. If an engineer was lucky enough to work in a studio with a three-track tape machine, they would be able to record in stereo, but only with three stereo panning options: left, center, and right.

These days, there’s a lot of debate about LCR panning, but when we look to these old recordings, we can see that LCR panning has its uses. The panning on some classic albums can sometimes sound odd to us now (bass was often panned hard left or hard right before engineers realized that this caused problems during vinyl pressing), but even with these limited options, every instrument and voice sounded like it belonged in the mix.

Using LCR panning for modern recordings might not be the best methodology for every mix, but it can be a good practice for clarifying the stereo setup of a mix, even if you just use it as a starting point. This practice can also help you decide which parts of the mix are the most important; if there’s a track that doesn’t fit well in an LCR mix, then maybe it doesn’t belong in the mix at all.

3. Mixing in Mono

Because stereo recording was so new in the ‘50s and ‘60s, many classic jazz albums were recorded in mono, and many jazz aficionados will argue (quite aggressively at times) that these classic albums sound their best in the original mono format. Whether you agree with the aficionados or not, the fact that anyone could prefer a mono mix over a stereo one is a testament to the amazing job the mix engineers did on these albums.

These days, unless you happen to listen to a lot of AM radio, you probably don’t hear a lot of music in mono. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t listen to your mixes in mono when you’re working on them. As a general rule, any mix that sounds good in mono will sound great in stereo, as mixing in mono will help you identify phase issues and force you to make better EQ decisions, since there’s no panning available to separate instruments.

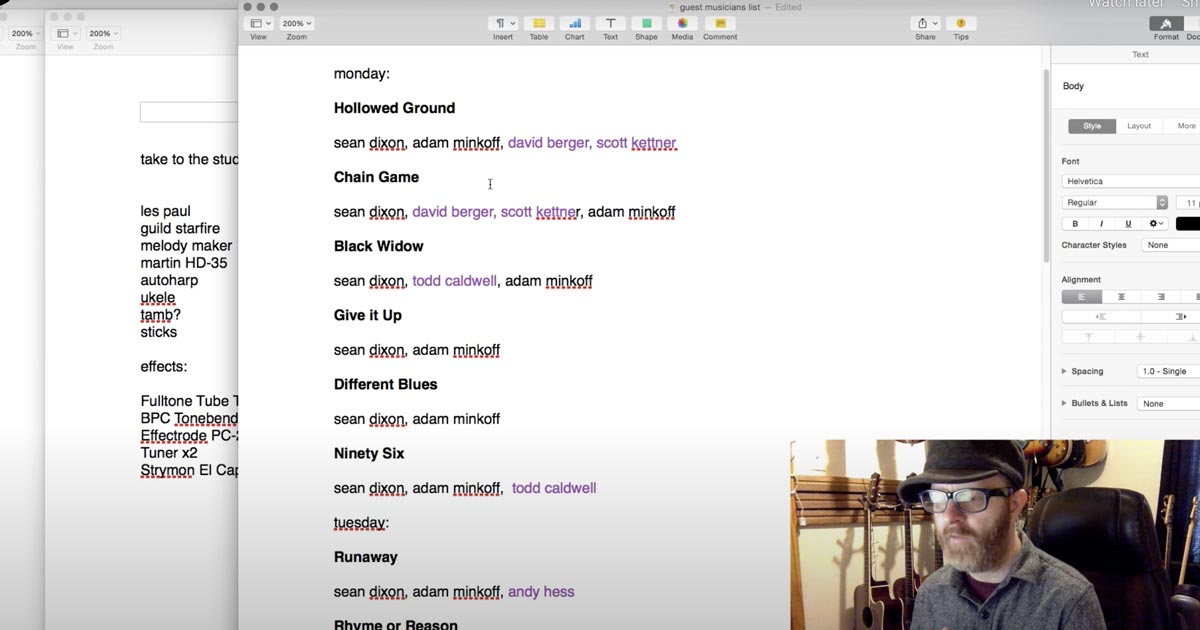

4. Live Mixing

Many early jazz recordings were made without a mix engineer, meaning that the albums were essentially mixed live as they were recorded. This means that not only did the recording engineer have to do an excellent job with their mic placement and preamp settings, but they also had to pay extremely close attention to what every musician was doing at all times.

Because of the limited headroom provided by analog recording equipment, engineers had to be prepared to ride gain knobs if instruments got too loud, and any “automation” would have to be done on the fly, as there was no opportunity to automate mixes once they were recorded to tape.

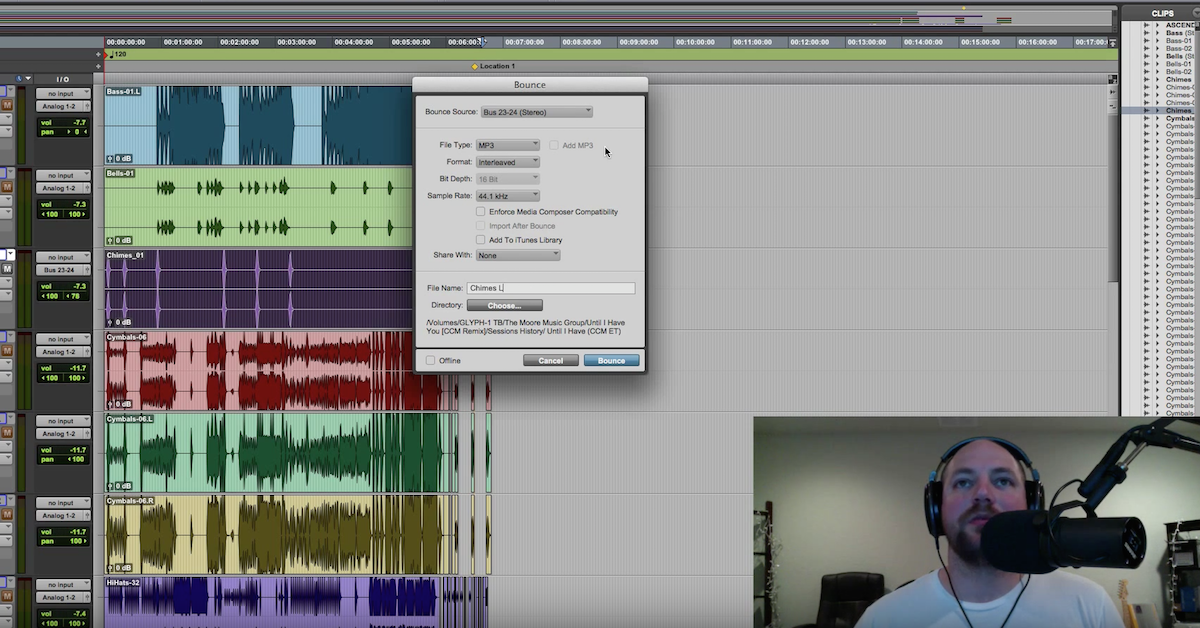

These days we can take a much more relaxed attitude to recording, but sometimes this relaxed attitude can get us into trouble. With the editing and mixing power of a DAW at our fingertips, we might not notice problems with a recording until it’s too late, only to discover that the “fix it in the mix” philosophy doesn’t actually work as well as we wish it did.

That’s not to say that you should be riding faders all the time when recording (digital systems give us much more headroom, making this practice largely unnecessary), but think about how different your recordings would sound if you paid careful attention to what every musician was doing, even after hitting the record button.

Conclusion

There are two different ways to listen to vintage recordings in a modern context. The first is to listen for certain characteristics as a guide for re-creating specific sounds from that time, and there’s certainly a lot that we can learn in this sense when it comes to vintage jazz.

The other way to listen, however, is to seek to understand the philosophy that led the recording engineers to achieve those particular sounds. If you listen this way, there’s plenty you can learn from these early recordings, even if you never make a jazz album yourself.

This is not to say that we should dwell on the past, but rather that we should look to the masters who have gone before us to glean some wisdom that we may be missing out on today.