How to Record a Full Length Album (And How Not To)

Today I’m excited to be launching the new Sonic Scoop video blog. We can go into more depth on things we’ve covered on the Sonic Scoop website, we can respond to questions and comments you guys have put up, so I’m very excited about this, and I think a smart place to start is with a topic that is going to be extremely useful to the musicians in our audience, and that’s about 50% of the Sonic Scoop audience, and it’s also a topic that the engineers and producers in our audience absolutely love, because they know what I’m talking about when I talk about this topic.

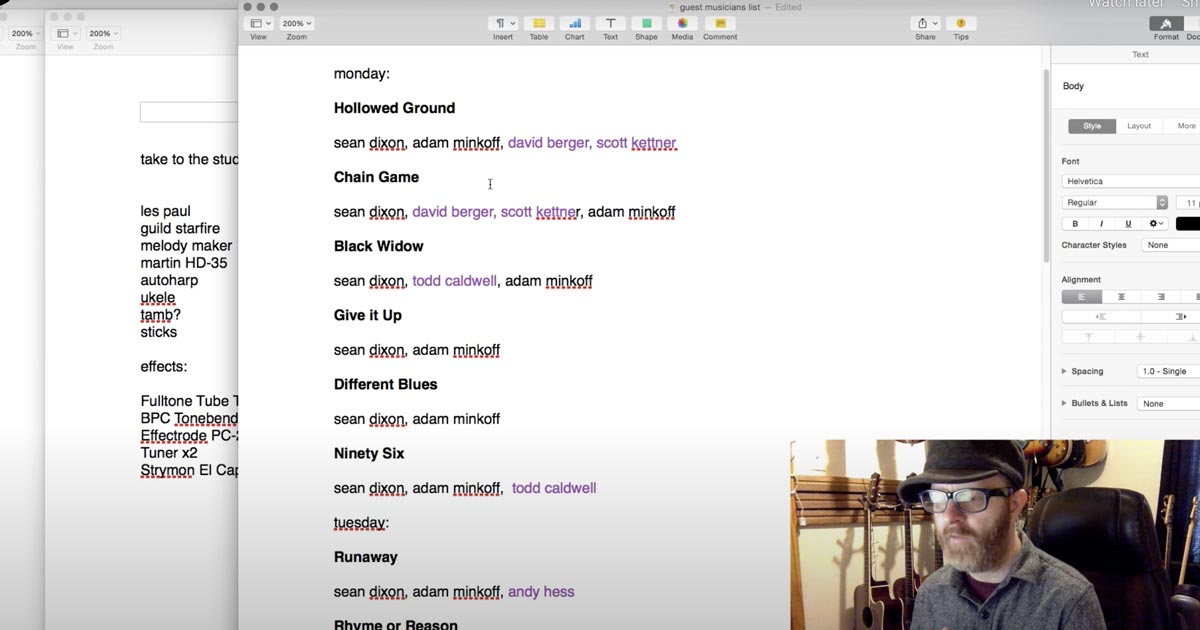

It is Best and Worst Practices for Recording a Full Length Album.

People are always asking me about this. Musicians, they’ll ask, “First of all, should I make a full length album? Is it relevant in this day and age of YouTube and Spotify?”

Actually, most musicians don’t ask me that, but I wish they did, because it’s a good question to ask and we’re going to explore that, but we’re also going to explore if you’re making a full length album the successes I’ve seen, what they have in common, and the failures I’ve seen, what they have in common.

This is something I was very interested in when I first started writing for Sonic Scoop. I wanted to talk to as many self released and independent DIY and major label artists as possible, to try to get a sense for what the ones have in common who succeeded and who developed audiences that were looking forward to hearing from them, and that enabled them to have sustainable careers, and keep on going back into the studio without freaking out about time and money.

I also wanted to explore those bands and self released artists and independent artists, major label artists that kind of fizzled out. You know, the band next door you know who had so much promise, they seemed so talented, and they printed out this box of 1,000 CDs, the proverbial box of 1,000 CDs that is still to this day 10 years later sitting in the bottom of their closet.

I think the best way to take a look at it is to go under the hood and think about the three different ways that artists usually approach making their first full length album, or their first big release. Talk about the pros and cons of each and where you can go wrong.

The first approach is the DIY approach. The second approach is what I’d like to call the conventional approach, and the third approach is what I’d like to call better than either of these if you are a new self releasing artist, and we’ll get to that in just a minute.

So the first one, DIY approach. DIY is often a misnomer. The most successful DIY artist I’ve talked to, and I’ve interviewed a lot of big ones, they’re often a lot less DIY than you think. They’re not doing everything alone, they have help in many different places.

When we think of DIY when it comes to recording, we’re thinking of someone mostly recording themselves on their own system of some kind, and the thought process behind the DIY recording goes something like this.

“Wow, going to a studio to record with some experienced engineer/producer person, that sounds really expensive. I bet you that I could just buy a whole bunch of that gear and I could kind of keep my costs low, I don’t need the fanciest gear, and I know I’m not going to spend any much more than the amount that I paid for in gear, and I won’t have to have some jerk engineer glaring at me the whole time I’m making a record.”

I get that, I sympathize with this approach, there are definitely jerk engineers out there. I think you could find one who’s not a jerk engineer, but I understand this approach and I’m sympathetic with it in part because I’ve done this and so many of the audio guys I know have gone through this approach at some point.

The audio guys and gals who are behind the consoles today, so many of them were artists who thought, “Oh, I could do this better, or maybe just more comfortably if I recorded myself.”

So it’s a valid approach, but there’s a couple pit falls here. Here’s the first one. Remember I said those audio men and women, so many of them started off as musicians doing their own projects and recording it? Well here’s the thing, they’re not really musicians any more. They became audio people.

That’s not a fate worse than death or anything, I’m happy being an audio person, but if you want to be a musician, if you want your involvement with music to be singing or writing, performing, creating new songs, putting something out there that didn’t exist until you made it, until you created it, if that’s what you want to do, then don’t become an audio guy.

Right? This actually dovetails nicely into the other big pit fall, which is the biggest cost is not reflected in the price tag. That price tag can be high, right? If you’re planning on recording several musicians together, maybe drums, you need several inputs at once, I would say a kind of minimal decent quality, but not crazy fancy and not super cheap system is probably going to cost you around $5,000.

This is not top shelf, this is you need basic studio monitors to hear what’s going on, you probably need a few sets of headphones if you have several musicians playing at once, you’re going to need an interface to get multiple channels in at once, so each of those channels is going to need a mic pre, you’re going to need several microphones, mic stands, mic cables… $5,000 is a low figure.

That doesn’t even include the room. Where are you going to put this stuff? Are you going to treat the room? Are you going to spend a couple of thousand dollars sound proofing it so your neighbors or your family don’t kill you? Are you going to be able to put up any absorption or acoustic treatment like we have to make every instrument in that space sound great? So those are things to think about, but the biggest cost isn’t even reflected in that price tag, and that is opportunity cost. Opportunity cost is a term economists use that means every hour you spend learning how to use all of this stuff is an hour that you can’t spend writing songs, playing shows, practicing your instrument, networking with the journalists, and the PR people, and the label people who might become your allies and help you really get your career going.

So I wouldn’t say that this is a cheaper approach. It almost never really is cheaper than going into the studio, unless you’re able to do everything yourself with just one mic, some software, and you’re kind of one man band situation. Maybe it could be cheaper. I don’t think it’ll be quicker. You results may or may not be good, you’re probably going to have to spend quite a while to get great results.

I mean, so many of the audio engineers that we knew were in the field five years before they really feel like they knew what they were doing with a compressor, so I don’t know how long you want to take to learn this.

Approach two, I would call this the conventional approach. Now, the conventional approach is let’s go into the studio and make a recording. This could be a hybrid where you do some of it in your own overdub room. You just buy a little bit of gear, enough to kind of offset some of the costs of the big place, and then you do some of the most essential stuff in the big fancy place, with a really competent engineer or producer, and that’s a great approach as well, but there are some trade offs here, and here are the things I’m going to warn you on.

If you are doing this for the first time, chances are you have some kind of job you’re working, or maybe you’re in school, and you can only devote a couple of days a week to going into the studio to record this big album project.

So let’s think about this. To be realistic, it will probably take you to do — let’s say ten songs, which is often enough, people say, “I want to do a full length album!” We’ll get to whether or not that’s the best idea to start with, but they’ll say, “I want to do ten songs. Maybe we can play through the whole thing in a day and then mix it the next day.”

It doesn’t work that way. It doesn’t work that way. You can go fairly quickly, but I find that when new artists go into the studio, it almost, without fail, takes about the same amount of time, I find, that new bands can often record three, maybe four songs in a day if they’re just doing basics.

Meaning they’re getting the drum tracks, maybe the bass tracked, maybe a scratch vocal track, hopefully they’ll keep some of it, maybe some guitar tracks, maybe they can get three or four of those in a day with a kind of live feel they want to add to.

Then after spending two or three days getting the basics, you might need another two or three days getting your instrumental overdubs, probably at least a couple days to do vocals, maybe more. Again, when you’re under the studio microscope and you’re doing multiple takes, it’s really hard to sing an album’s worth of material in one day.

So this often takes a lot longer than people expect, not just because when we add all that together it’s often ten days, it often takes longer than people expect, because how long will it take you to set aside ten days if you are a new artist who isn’t making money off of being an artist?

Chances are you have some kind of job to pay the bills, maybe you have school, the most unfortunate thing about the second approach is that so often, artists will after months and months and months of spending a few days this month, a few days the next month, a few days the following month, they’ll have a release of these ten or twelve or fifteen songs to present to the world, and nobody cares.

Because nobody has heard of them. It’s the first thing they’re ever putting out there.

Because of this, I suggest a much better way, so you don’t end up with the proverbial box of a thousand CDs sitting in your closet with the website that no one is visiting, with the Facebook page with the three likes on it. This happens so often because artists are putting all of their focus into creating this big product before they have an audience, where I really think you’ve got to take the 21st century approach.

This really human approach that the technology enables. This approach is to record one song, start to finish, in one day, and release it.

I call it the song-a-day approach. But there’s a catch.

Doing this in the studio with a great producer is going to help you realize an amazing song. It’s going to take a lot of up front pre-production work. So pre-production is where this step three, the approach starts.

What is pre-production? Well, you can get yourself a simple audio rig. It could just be a recording on your phone, or it could be as simple as the built-in speaker or built-in microphone on your laptop, and record the band in a room, or you could be doing overdubbing on a basic DAW system. You can get a decent interface and a decent mic and layer the stuff on.

Whatever it is, you want to get to a point where you say, “Wow, this song sounds so great, I wish we had recorded it for real.”

And then when you have it at that point where you’re almost like, “ah, that’s great! Damn, I wish we had recorded that for real.”

Then you’re ready to go into the studio and in one day, using that roadmap you created during pre-production, record one song that day. You might be able to do more. You might be able to do two if you’re really lucky, but let’s focus on just one song. Spend the first half of the day, maybe three quarters of the day after the lunch break recording the song, and then spend the last quarter or half of the day mixing it.

If you need to come back in the morning for touch ups, great. Maybe the person helping you mix it can leave it up there on the desk. The beautiful thing about this approach is A, you get a super well realized song. You’re not even taking that song into the studio until you know it so great that it’s ready to be put under that microscope. All of the pieces are fitting together, and now, you just need to do it in a way that’s going to realize the song to its maximum potential.

So that’s beautiful part number one. Beautiful part number two of this process is you can release it right now. If it’s your first major recording, I would just put it up there for free. Get it up there, See if you can get people interested, see if you can start building allies, fans, other bands or artists that you can perform with. Journalists and PR people and label people who could become your allies, care about your project, and help get the word out.

Then the next month, you can do this again, and you can have another song to release to the world next month. So you’re starting to build some buzz, starting to build some traction, and then the third month, you can go in and do the song-a-day approach again, right? You spend the rest of the month kind of honing this thing, and then go in and just do it, and release it.

After four months of doing this, you know, just over a season, you will have put out three or four amazing songs that are the best you’re capable of doing. At the end of those three or four months, I’ll be darned if you don’t have some kind of traction, some kind of allies that you’ve created in this world who are going to help you spread the word about your music.

And you know what? Over these four months, all of this is put together, you could be in the background working on the basics for more song, and you can do the more conventional approach for four or five or six more songs, and then you’ll have eight or nine or ten songs that you can release to an audience that has been waiting for the next thing.

They can’t wait to find out when your next release is going to be! So this is the approach that works in the 21st century. I love it because the technology is empowering us to take this more human approach. How human is it as a musician to say, “well, once a year, I’m going to just do balls-to-the-wall music, and for a little while, and I’ll just do it really intensely, and then gone.”

No, you should be doing a little bit every day. A little bit every week, a little bit every month. You’ve got to make music a part of your daily life, if you want to be the kind of person who makes a sustainable career, whether it’s full time or part time, or even just for a bit, if you want to make a sustainable career out of music.

Now, once you’ve done this approach with some success, you know, the conventional approach may work for you now that you’ve built up an audience. Or, the DIY approach may work for you. Maybe you got real into the audio side, and you want to be the person turning all the knobs, that’s fine too, but if you’re just starting off as a musician, I would really sincerely recommend you think about this song-a-day approach.

You can read all about this approach in an article I wrote for Trust Me, I’m a Scientist, it’s called “How Long is this Going to Take? The Time and Costs of Recording a Full Length Album.”

Hey, thanks for hanging out here at Joe Lambert Mastering with me on this Sonic Scoop video blog. You can always subscribe and get the newsletter at SonicScoop.com, and I look forward to seeing you.