5 Strategies for Creative Discovery in Music Production

Article Content

Successful music producers, composers, and musicians recognize the need for new inspiration and creative approaches. Players are constantly learning new repertoire, developing new techniques and refining existing facility on their instrument.

As a guitar player with over 50 years of experience, I can attest that you need a constant influx of new playing challenges to keep things fresh. My recent endeavor is to learn a slew of finger-style techniques, which is challenging having been a slave to the pick for so many years. But new challenges instigate creative growth and provide new ideas.

We are taught from a young age that the creative arts are all about expression; expressing your feelings and emotions, or even lack thereof. But the word “expression” carries with it certain fixed concepts that can be viewed as limiting. To express something means the thoughts or feelings must already exist in your consciousness or subconsciousness, and the tools you use to express yourself are generally preexisting as well. That makes sense; to express yourself with any degree of eloquence and fluidity you need a firm grasp of the language and the technical facility to execute a coherent and engaging musical idea.

But one thing that is missing from this focus on expression is a concept that is elemental to anyone that decided to seriously pursue a creative field — discovery! Every composer, producer, or player can name artists that they personally “discovered” at some point that had a lasting impact on their work. I would argue that this feeling of discovery (which can be related to hearing a new genre, artist, or even some sort of audio processing technique) is a powerful impetus for starting a new career and can provide fresh creative ideas for established creators.

It’s possible to view creative production on a sort of spectrum with expression on one end and discovery on the other.

On the expression side, we look inward — exploring our emotions, feelings and intellectual thoughts. We draw upon our existing skill set to realize new work: playing and production techniques, knowledge of harmony and musical form, our understanding of genres and their musical languages. Our musical taste is sort of an amalgam of all these things.

On the discovery side, we seek out the unfamiliar and explore new territory. This might be in terms of genre, playing or production techniques, approaches to composition or new sounds in general. For the process to be enriching we need to be completely open to the new, and cannot allow existing tastes to summarily dismiss things that might seem initially objectionable.

This does not suggest that expression and discovery are completely isolated ideas. There are certainly unlimited ways to express a musical idea using existing skills that can adhere to certain individual taste or style. Discovering a new approach within that context is certainly possible. Likewise, it is possible to find new ways of expressing yourself with newly discovered sonic content or musical ideas. The reality is not an either/or scenario, but rather a decision to skew the process toward one end of the spectrum or the other.

It has been my experience that most artists lean towards the expressive side of the continuum and never really give the act of discovery enough attention. This is unfortunate since discovery was undoubtedly the reason you’re an artist to begin with. Probably the most well-known composer of the 20th century that shifted things towards discovery was John Cage. His use of indeterminacy and chance spawned a whole new way to write and to think about music and sound in general. In my early days, I was admittedly obsessed with Cage’s work and while my creative output ultimately took its own course, I remain indebted to his adventurous spirit and his willingness to experiment with sound has remained a deep concern in my work.

So in this article I’ll suggest a few strategies that might nudge, push, pull, shove, drag or cajole you to explore the other end of the creative spectrum.

1. Randomness and Chance

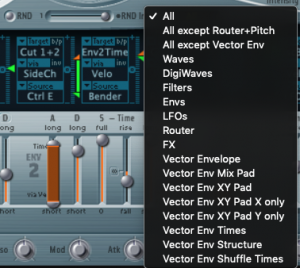

There is nothing more effective for removing your personal bias or habitual choices than using random processes or chance. Realize, however, that relinquishing control of choice is not absolute. You still have to establish the initial parameters of whatever process you’re using. In a synth, for instance, there may be a random button with a user-selectable palette of what will be randomized and by what percentage. Depending on how aggressive you want to be, you could generate subtle variations on an existing sound or something completely different and unexpected. Or, for that matter, it could be something completely unusable. Recognizing the “usability” of the results will depend on your willingness to try something new and/or how closely it aligns with your existing taste. So you are never operating solely on one side of the spectrum or the other. It is a continuum.

Below is a randomizing menu in Logic Pro’s ES2 synth:

The Polyplex instrument in Reaktor offers randomization in myriad parameters — everywhere you see the dice icon. In the intuitive GUI design, the farther to the right you click in the dice slots the more extreme the degree of randomness that results.

There are countless decisions to be made in music production. Some are small and less significant, and others can dramatically affect the result. Cage was known for using the I Ching, an ancient Chinese system which is “grounded in cleromancy, the production of seemingly random numbers to determine divine intent.” He used the system to determine myriad musical decisions that would normally be made by the composer, instead letting the process dictate the result.

Serialism (a descendant of Dodecaphony or 12 Tone Music developed by Arnold Schönberg) was applied by composers such as Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen to serialize choices of dynamics, articulation, duration and even pitch. Choices were culled from pre-established lists of possibilities and in the strictest sense, applied without the intervention of the composer’s intuition. This extreme aesthetic was the source of much debate at the time and the practice was largely abandoned eventually. But the idea of discovering new sounds and possibilities using randomness, indeterminacy, aleatoric processes and chance has remained in one form or another in contemporary music ever since.

2. Write on an Unfamiliar Instrument

Any instrumentalist knows that developing muscle memory (which is really long-term memory) is absolutely essential in order to execute musical gestures in real-time. There needs to be a direct and immediate response between thought (auralization) and music-making. But with composing this is not necessarily the case. In fact, writing on an instrument with which you have a large bundle of ingrained habitual techniques and gestures to draw from may carry a certain weight that could restrict your ability to think about all the musical possibilities. Most jazz players will admit they rarely play something they haven’t played before, but when it happens it’s magical. Of course, you create beautiful music with a large vocabulary, but if you don’t find a way to push your limits, you’ll never learn any new languages.

So if you normally write on guitar, try using a piano or vice versa. Try some sort of MIDI controller or program a sequencer using random procedures. The point is to remove yourself from your comfort zone and see what happens. You can even mess with your existing instrument to undermine your habits. Try using alternate tunings on a guitar or microtonal tunings on a virtual instrument. John Cage’s prepared piano pieces, Sonatas and Interludes, are a great example of usurping the natural expectations of pressing a piano key while still utilizing the technical facility a pianist develops from years of practice.

3. Misuse and Abuse

Software and audio plugins are designed with very particular uses in mind. The presets, controls and GUIs imply and dictate what can and should be done. But I believe the user should control the plugin and not the other way around. So try using settings that are extreme or don’t seem appropriate. Many students have asked me what the correct way to use a particular plugin is, or what are the correct settings. Of course the answer is if it sounds good it is good, and correct. Sometimes it’s good to set aside customary methods and see what happens. You can’t really break software (believe me, I’ve tried), so experiment! For that matter, as long as you watch the output and don’t hook things up too weirdly, it’s difficult to break audio hardware as well. In case you are unaware, there is a genre known as no input mixing that is based entirely on doing the “wrong” thing. Mixer outputs are routed back to inputs via AUX sends, creating an incredible variety of sounds without any source other than the mixer itself.

Another genre that encourages device abuse for sonic reward is circuit bending. See my article, “12 Experimental Approaches to Music Production & Composition” from May 2020 for more about this.

4. Self-Imposed Limitations

I wrote about this idea in another article a few years back. The premise is quite simple. Impose a set of limitations for composing, mixing, playing an instrument or whatever the activity in question is. It might involve restricting your playing to one string on a guitar, only using a certain set of plugins in a mix, mixing exclusively in mono, composing a melody using a restricted number of notes and or rhythms, etc. These limitations force you find good results in unusual ways and undermine habitual behavior. It can result in new discoveries that will transcend the scenario and become part of an expanded creative vocabulary. As a guitar player, I can tell you that the one or two string limitation does wonders for seeing the whole neck and playing across positions.

5. Sound Fragment Composition

One exercise I assign to first-year audio production and sound design students is to write a two-minute piece using only a very short sound sample (usually less than a second). It could be a plucked string or some other obscure transient. Aside from the limitation in the source material, any other processing can be used including time compression and expansion, sampling techniques, time and space processing, spectral processing, etc. This scenario short circuits the creative process and typical methodologies. It forces the composer to explore everything about that little sound fragment and exploit its possibilities in unusual ways. I’ve heard some tremendous results and I believe the experience has had lasting effects on the young minds I’ve made it my business to warp over the years. If you have never tried this I suggest giving it a shot. You may be pleasantly surprised with the result and at the very least you’ll have some fun.

Conclusions

Musical expression is inherent to music production and the composition process, and it undoubtedly comes naturally to anyone that has decided to live a musical life. But as I was hopefully able to communicate in this article, expression alone implies a sort of stasis in that we can only express existing thoughts and feelings. The tools we use for expression are often fraught with habitual tendencies that can, in the extreme case, inhibit personal and creative growth. When we first discover music there is an excitement so strong that it can change the course of our lives. At that point we are not actively expressing anything musical—it is pure discovery. I believe that refining your ability to express yourself musically, while continually renewing your sense of discovery will help you grow as an artist and lead you toward new and unexplored territory.

Check out my other articles, reviews and interviews

Follow me on Twitter / Instagram / YouTube