10 Tips for Mixing Background Vocals

Article Content

Great vocal arrangements can truly elevate a song, adding an immediacy and dynamics that pull the listener in. Mixing layers of vocals, however, can require a totally different approach from working with a lone lead vocal. In this article, I’m going to offer a few tips for how to handle background vocals in a mix.

1. Identify the Sound You Want

If you’ve read a few of my articles, you’ve seen me make a point like this before: it’s much, much easier to get a sound you like if you actually know what that sound is in advance.

There’s more than one way to have great sounding vocal arrangements in a recording. The genre, the song and the singers are all going to point to different approaches. So take a moment to think about where your backup vocals are at before you start throwing plugins on tracks. You might ask yourself some questions like:

- Is this a song with a clear lead vocal track, or more of an ensemble situation?

- Do the backup vocals support the main vocal part, or do they work independently?

- How do the background vocals fit into the structure of the song? Are they there all the time, or do they come in for certain sections?

The answers to these questions can vary widely from one song to another, which is exactly why it’s worth thinking about them before you start mixing. As always, it can be extremely helpful to have a reference in mind — a recording that you know has a vocal sound you like. You can use that throughout your mix process to gauge whether your choices are leading you in the right direction.

2. Have a Pan Plan

Once you’ve got a vision for how your background vocals are going to sound, one of the most basic but effective tools to help you get that sound is panning.

A very common approach to background vocal mixing is to have them add a sense of width to choruses and the “bigger” moments in a song. Britney Spears’ “Baby One More Time” is a classic example of this type of backup vocal mix:

In that mix, the verses feature more minimal vocal arrangements that feel centered in the stereo field. Backup vocal layers enter in the pre-chorus and build into the chorus, adding width to the vocal part and intensifying the dynamics of the song.

Of course, that’s just one example for one type of song. D’Angelo’s “Till It’s Done” features more minimal vocal layering that stays close to the center, creating a sense of separation in the mix. Skip to 2:58 to hear the clearest example of this.

A song with more movement in the vocal arrangement might benefit from panning that highlights distinct layers by giving them different placements in the stereo field, like you can hear in the Beach Boys’ “All I Wanna Do:”

The point I’m trying to make with these examples is that approaches to vocal panning are incredibly varied. There isn’t one magic bullet approach that will work for any song, but referencing vocal mixes you like can help inform the choices you make.

3. Favor the Strongest Takes

Another very simple step you can take to strengthen background vocals is to pick a favorite take and make it more prominent in the mix when parts are doubled.

There’s no law that says you have to mix all doubles at equal volume. If a given vocal line is double or triple tracked (or more), find the strongest performance and mix it in louder than the tracks doubling it. You’ll probably find that the vocal part as a whole sounds tighter as a result. This approach becomes more and more important as you add additional backup vocal tracks, keeping things clean and in tune.

4. Use Formant Shifting for Color and Depth

One of my favorite tricks for thickening up a layered backup vocal part involves formant shifting some of the voices to sound “bigger” or “smaller.” This approach works especially well when the vocal arrangement is all coming from one singer layering overdubs.

If you aren’t familiar, formant shifting is a sonic artifact that naturally occurs as a result of pitch shifting — originally achieved by speeding up or slowing down tape playback. As the pitch of a sound is shifted up, the source appears to become smaller, or bigger when the pitch is shifted down. With digital processing, we can separate that sense of size from the actual pitch of a sound, and that’s what formant shifting is all about.

If you have a group of layered backup vocals, try formant shifting some of them up or down. One semitone or less is often enough for subtle thickening, though around two semitones can yield cool results if realism isn’t a necessity. Play around with settings, and you’ll know pretty quickly how far is too far. I will typically shift upwards for high harmonies and downwards for low ones, but that isn’t a hard and fast rule. The goal here is to differentiate voices from one another so the group sounds larger. If things get “glitchier” than you’d like, back off. A light touch can go a long way with this trick.

A kind of extreme upward formant shift of 1.4 semitones

My favorite plugin for pitch and formant shifting is Little AlterBoy by Soundtoys — but there are plenty of other great options for this sort of processing. Waves Vocal Bender and Polyverse Manipulator stand out as more “effect-y” choices, while Celemony Melodyne and Antares Throat Evo are more versatile and natural sounding.

5. Use Short Delay for a Bigger Sound

Another more conventional trick for thickening up the sound of a vocal group is to use short delay — I’m talking very short. The goal is to create the sound of a vocal group where a few singers are consistently a few milliseconds late.

Delay values somewhere in the neighborhood of 20-60 ms tend to work well — just long enough not to create phase problems but short enough that the delay doesn’t sound rhythmic. I’ll use a light touch with this sort of processing, as mixing in too much makes the delay noticeable for what it is.

This trick works really nicely in tandem with the previous suggestion — formant shift some voices and add some short delay, and you might find that your backup vocal “group” sounds much bigger.

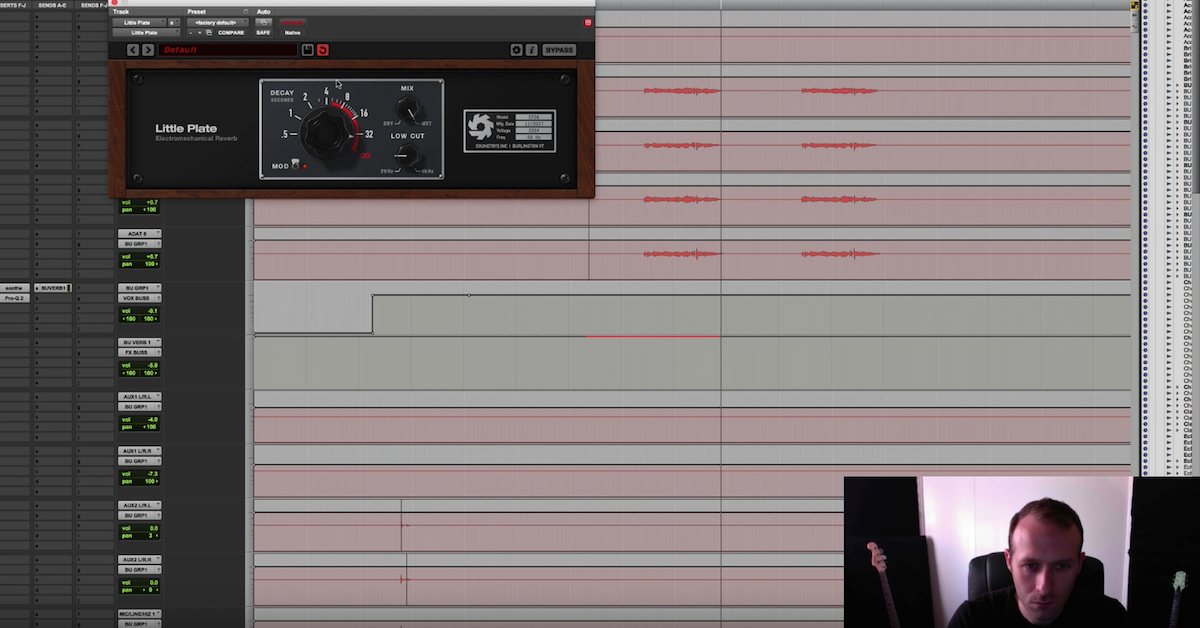

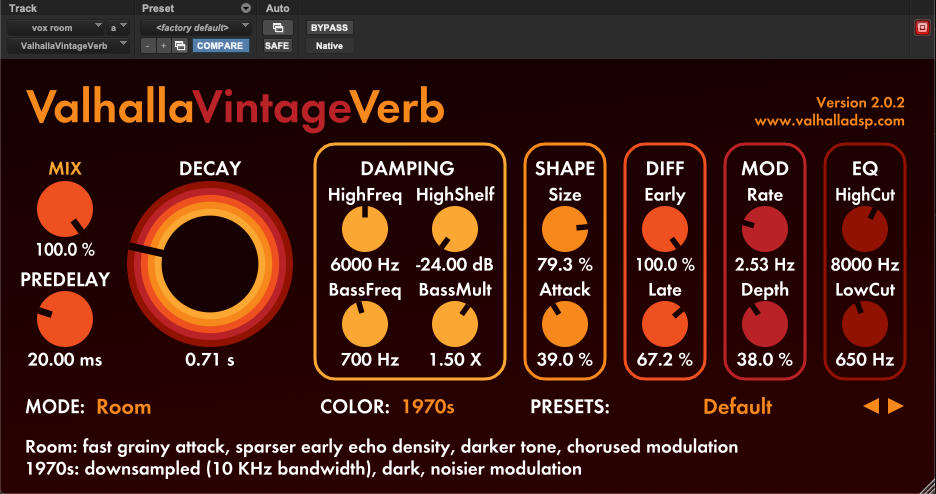

6. Glue Voices Together With Room Reverb

When working with layered vocal overdubs, it’s pretty common to mix them to sound like a group of backup singers did a take together around one or two mics. In those cases, room reverb is your friend. I’ll typically use a room reverb with a very short decay — around or less than one second — and mixed down to the point of barely being noticeable. It isn’t common for my backup vocal room reverb buss to end up any more than 12 dB below the dry tracks.

The goal of this sort of reverb is realism. A dozen close-mic’ed vocal overdubs done by the same person has a distinct sound. Putting that multitrack in a “space” can help it sound more natural, adding a sense of depth and openness.

This trick stacks well with the last two. It also works in tandem with a more dramatic reverb — plate or chamber reverbs are great choices. The room reverb will create a sense of realism, while the chamber or plate adds a classic, lush reverb tone. The room reverb will still work to glue the vocal layers together without being overtly noticeable in the mix.

7. Go Heavy With the De-esser

Things can start sounding really cluttered when a dense vocal arrangement features a bunch of sibilant consonants that all arrive at slightly different times. Even experienced vocalists can have trouble nailing the timing of “s” sounds that land at the end of words, and less-than-tight performances can tend to make things sound pretty messy.

For that reason, I’ll typically be pretty heavy handed with a de-esser on a backup vocal track. As long as there are one or two more subtly processed tracks driving the articulation in the vocal, the results can still sound natural without getting messy.

It can also be helpful to use plugins that can tame aggressive transients. Eventide Split EQ allows you to EQ transients separately from sustained sounds, and Oeksound Spiff is an “adaptive transient processor” that allows for a ton of control over transient information. Both are excellent options when more percussive consonants are a problem.

8. Buss Processing is Crucial

It’s not unusual to hear a fair amount of independence from the most prominent vocal in a backup part. Still, in most cases, those supporting vocal layers are more likely to function as one unit in the mix rather than a bunch of distinct elements.

In most cases, backup vocals are best treated together, with the most basic and crucial processing happening on a buss. Whatever other signal flow twists and turns are necessary, send your backup vocals to one submix. This is where they’ll get the bulk of the most basic processing that helps them sit in their proper place in the mix.

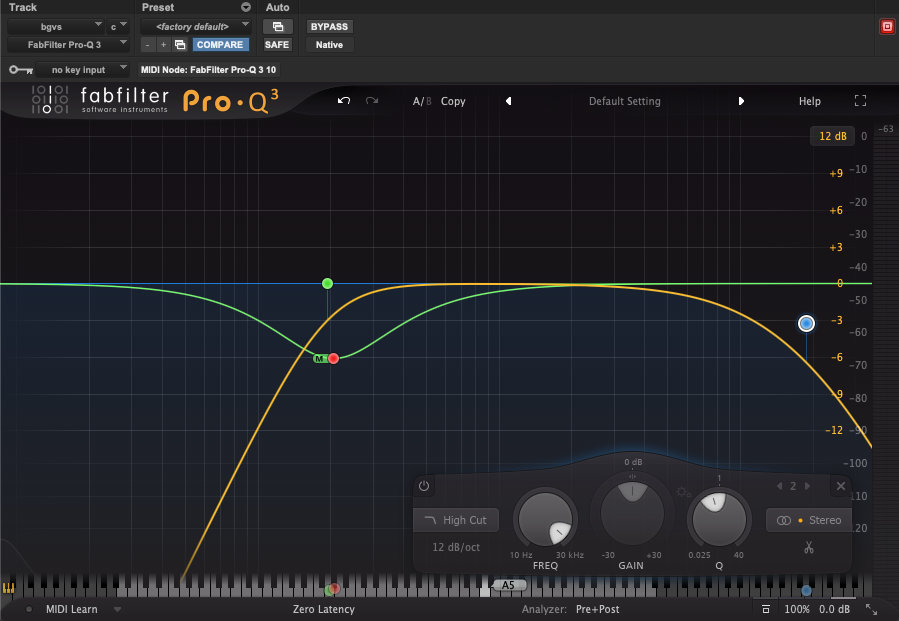

9. Use EQ to Give the Lead Vocal Space

On my backup vocal submix, you’ll usually find some gentle EQ intended to help those additional vocal layers support the lead without getting in the way. I’ll look to make cuts in the midrange wherever the lead vocal needs breathing room. Usually, that’s between 150-400 Hz where the body of the lead will sit, and 2 kHz or so to help the lead vocal have a distinct sense of articulation.

If the backup vocals live on the sides of the mix, I’ll make those midrange cuts down the center channel using a mid/side EQ. The lead vocal can stand out in the center without compromising the fullness of the backup too much.

Additionally, high and low-pass filtering can be crucial to get backup vocals sitting right in a mix. High-pass filters, as always, are great for cleaning up low frequencies that add nothing to a backup vocal and only add mud to a mix. Low-pass filters can help tuck background vocals behind the lead — letting it sparkle in the spotlight while they sit in… you know, the background.

Background vocal buss EQ – high and low pass filtering, plus a generous lower midrange scoop down the center

10. Use Gentle, Medium-Fast Compression to Keep Them in Check

Sticking with the topic of buss processing, some gentle compression on a backup vocal submix is typically crucial to keep those vocals full sounding without getting overbearing.

Almost all my mixes with vocals will feature a compressor on the backup vocal group buss, set at a light ratio to reduce around 2-4 dB at the most.

Background vocal buss compression — gentle ratio, medium fast attack, and release timed to the song

My go to for this purpose is UAD’s Neve 33609 plugin. It has attack times exclusively between 3-6 ms. Medium-fast attack times in that range can make a compressor clamp down on a backup vocal fast enough to get it out of the way of the lead vocal, drums or anything else that needs transient articulation in a mix — but not so fast that they disappear. I’ll time the release to suit the tempo of the song, aiming for a sweet spot between pumpy/unnatural (too fast) and robbing the vocals of presence (too slow).

Conclusion

Background vocal arrangements can make mixing feel more complicated, but there’s no reason that has to be the case. Like working with multitracked drums or any of the other common stumbling blocks in mixing, having a vision for the sound you want and making the most out of the material you have will go a long way. Hopefully, after reading this article, you have a few new ideas about how to approach the vocal arrangements in your next mix.