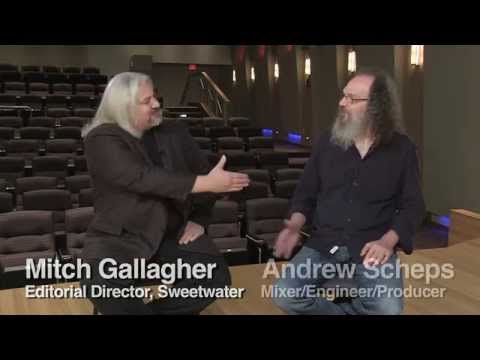

Interview with Engineer/Producer Andrew Scheps

Andrew: Hello. Good morning. Absolutely, thanks for having me.

Mitch: Mixer, engineer, producer, Metallica, Black Sabbath, Adele, all kinds of great credits. We’re happy to have you here.

Andrew: Thanks. Thanks for having me.

Mitch: You bet. You’re here on behalf of Royer Labs and Mojave Audio.

Andrew: Yep.

Mitch: And you were doing a presentation I want to talk a little bit about, but let’s step back, talk a little bit about how you got into the business. How did you get started as an audio professional?

Andrew: Well, I sort of discovered live sound because I wanted to be in a rock band, but I played trumpet, so there’s a little bit of a disconnect there, so I started doing sound for bands, and then discovered studios, and fell in love with it immediately. Saw my first console and knew, “Okay, that’s what I want to do.”

Went to University of Miami, did their four year recording program, it’s part of the music program down there, and then out of college, got a job working for New England Digital, we made the Synclavier way back in the olden days. Then from there, just started making records. Just, that’s it. Just went independent, and scrounged and clawed my way to the middle.

Mitch: So how did you get in on your first session? How’d you make that break into the studio?

Andrew: Well, fortunately, actually coming from the Synclavier world, when I stopped working for Synclavier, I had met lots of people who had them, and I knew how they worked and how to program them, so I actually started and got a lot of work as a programmer, and went from Synclavier programming to sort of general synth programming, and then from there into editing when disc recording started up, and from there into Pro Tools, and all the while, assisting and doing as much engineering as I could, and finally, when budgets started shrinking to where you didn’t have an engineer and a Pro Tools guy, I was both, and then…

Mitch: There you are, you were perfectly positioned.

Andrew: And off it went. Right.

Mitch: Nice, nice. So you have worked a lot with Rick Rubin over the years. How did you make that connection?

Andrew: I have. I’ve been — I’d actually gotten calls a couple of times to do some either Pro Tools editing or programming that just didn’t work out schedule wise, and then the first project I did with him was a Saul Williams record, Amethyst Rock Star, and it’s almost 15 years ago now, and that I was brought in, because they had done a lot of tracks on MPC60, and then they’d recorded things to tape, and now they couldn’t get it to sync up, so I sort of came in to troubleshoot that, and while I was there, did some Wu Tang remixes that needed to be done, and just sort of was in the room and anything that came up, like, “Yeah, I’ll do that. I’ll do that.” So it’s turned into a pretty long relationship, and it’s great.

Mitch: Nice. Nice. So the moral of the story is never say no?

Andrew: Never say no, and if you’re everywhere all the time, eventually you’ll be in the right place at the right time.

Mitch: Right. [laughs]

Andrew: And be prepared. Yeah.

Mitch: So one of the most recent projects you guys worked on was Thirteen with Black Sabbath. Can you tell us a little bit about that project?

Andrew: Yeah, I only mixed the project, I didn’t track it, so unfortunately, I didn’t really get to interact with the band too much, which would’ve been pretty amazing, but I think kind of the main thing about that record was trying to recapture sort of the spirit of their first four records, which their first record was done in two days, they tracked it in the first day, and mixed it on the second day.

To recapture that kind of spirit of them as a band, you know, a real performance, but you know, obviously have it live in the world that records live in now, so a lot of that record was cut live, a lot of the solos are the solos right off the floor while they cut the track, so it was awesome. Really, really simple. Very few overdubs — I mean, some of the songs had no overdubs, so it was pretty amazing.

Mitch: That had to be pretty cool to walk in and push the faders up and that stuff.

Andrew: Yeah, and I mean, that’s always amazing, pushing up faders like that, and you know, the drums, Brad Wilk played drums, so he’s an amazing drummer, when you start pushing up the guitars, it’s like, “Oh, it sounds like Tony Iommi,” and then you push up the vocal, and it’s like, “It’s Sabbath.” It’s not a band that sounds like Sabbath, it’s Sabbath. That’s pretty cool.

Mitch: Right. Right, right. So you had mentioned they’d kind of wanted to recapture that spirit. Did you go back and spend a lot of time with the old records to kind of get a direction for where you were going to go with the mixes?

Andrew: Not so much actually, it was more before I even got the first song to mix, I just listened to the first four records again, and I hadn’t really sat down and listened to them in years and years, and I realized immediately, sonically, there wasn’t really anything to take away from it, because that was of a time and there’s no way we’re going to make the record sound like that, but it was really getting a sense of it being four guys in a room, and not it being a slickly produced, put together record.

So really making it sound like a record as that needs to happen now, but hopefully, you get the idea that it is four guys playing, and that is what you’re hearing.

Mitch: Right, right. Now, when you’re mixing, obviously, you come from a high technology background, Synclavier, Pro Tools, and you’re working in that digital world, but you also in your studio have a vintage console and racks and racks of gear, so you’re really pursuing that hybrid approach, can you talk a little bit about that?

Andrew: Yeah, it’s actually really interesting the sort of twists and turns as the technology comes, I mean, as the hard disk recording technology sort of came into being, Pro Tools was able to do more things, and stuff like that. It was easy to just immediately embrace it, because you could finally do something much quicker than you used to be able to on tape, and stuff like that. And you didn’t give a whole lot of thought to the sonics of what was going on, and back then, the digital technology was not so very good sounding, so then going back to a more analog hands on mix process, and in the mean time, mixing like that, and now digital has caught up sonically, so when I mixed the Sabbath record, that was completely on a console.

I mean, it could’ve been — I was using Flying Faders automation, so that dates it around 1994, but the rest of the gear, 1979, 1980 for the most part. But obviously, the tracks are running off of Pro Tools, and I’m automating delays, either using something like a Moog 500 rack delay through MIDI, which you couldn’t have done awhile ago, or plugins and things like that, but now, since then, just because of the way the mixing process is, and the creative process of working with bands who want to start mixing before they’re even done recording, and their mastering deadline is Thursday, but they’re actually tracking on Tuesday.

I’ve actually started moving more back into the box, because sonically, it sounds amazing, but gives me all of the flexibility, so it’s strange, you can make arguments for an against every method of working, and you know, I think the thing that I always try and keep in mind is that nobody cares what I mixed it on, nobody cares what it looked like, nobody cares what lights were on, they just get it coming out of the speakers. If that’s awesome, it’s awesome. If it isn’t, I could tell you all day what console I used, and you wouldn’t care. That’s a very long answer to that question.

Mitch: No, that’s great. That’s all good. So what is it that dictates the choice for you? So if you receive a track from a band, and you say, “Okay, I need to have EQ on this vocal,” how do you decide whether it’s going to be a plugin or you’re going to go out to a piece of hardware?

Andrew: Well, when I was spread out on a console, generally, I would use a console EQ for broad strokes, a very musical EQ. You don’t do that much removal of frequencies on a Neve. You do much more addition of frequencies, because it just sounds great, but it’s also broadband, there’s not a lot of precise control, so if I needed to take care of a harsh frequency in the cymbals or something like that, that would be in the box, if I need to do a — I want to put a happy face EQ on this thing, that would be on the board, and now that I’m pretty much in the box over the last six months, it’s kind of the same choices, but it’s just all plugins, and every once in awhile, I use outboard gear on hardware inserts, just because I really want a specific thing that I can only get out of a piece of gear, but there’s just certain EQs that are musical and happy, and there are certain EQs that do a job, and it just depends what’s going on.

Also, because of the brilliant Al Schmitt quote where he just said, “I don’t use EQ or compression,” and then spending two days with him watching him record a big band without EQ or compression, I’ve now stopped using EQ unless I feel like I really have to, because I think when you mix, one of the first things you do is, “Alright, let me go through and EQ everything,” and you don’t have to, actually. It’s a really interesting sort of limitation to put on yourself that you will not EQ unless you have to EQ, and that makes you really start to think about panning and balance and arrangement in ways that you don’t when you could just carve out spots for everything, so.

Mitch: Right, right. And I would expect there’s also just some habit. When I hear a kick drum, I put this on it.

Andrew: Absolutely. Absolutely, and the idea of, “Oh, I always use this on kick and I always use this on vocal,” it’s one of the great things in the box is that it’s so easy to try 50 different things on something, and save chains of 5 pieces of gear as plugins, and just say, “How’s that? No. How’s that? No. How’s that? No.” And it’s stuff you spent a lot of time going through once, and then you can just use it as quick palates, and stay creative while trying to use all kinds of stuff.

Mitch: Right, right. And you’re working primarily from your home studio, correct? How are you able to make the transition from working in commercial studios to working at home?

Andrew: That’s really easy, people don’t have money. [laughs] So when you don’t have money, you have to own the means of production. I mean, seriously, that’s a huge part of why my studio exists is bands that could not afford to book Ocean Way or the Record Plant, and as much as I love going to studios, because I love supporting the idea of studios, and I love having the support staff, and I love having larger tracking rooms, when there’s no money for it, I can’t spend money to make a record unless, you know, it’s on my label, which I spend money to make records for that, but you know, I can’t lose money, so it became a necessity, and now I love it. I would never mix anywhere else. I walk in and I start mixing. I don’t have to figure anything out, and I probably work twice as fast as I would anywhere else.

Mitch: Nice, nice. And you’re — I would say on a different level, but in a situation that’s similar to what many people who are watching this video are in, where you have a studio that’s in a room that wasn’t purpose built as a studio, correct? So do you have any suggestions or tips or approaches people can make to make a room that’s not designed to be a studio work as a studio?

Andrew: Yeah, I think one of the main things that sometimes people don’t remember is that control rooms and recording rooms are totally different animals. So first of all, forget about trying to be the live room at Ocean Way. You’re building a listening room for your control room, and really, if you think about it, some of the best places you’ve ever heard music played back is in a living room, and the idea of my control room — I’m lucky because it’s a very big room and it has high ceilings, but for me, it’s that the room doesn’t sound like anything, so I hear my speakers, and that’s it. I’m not trying to get certain acoustic things out of the room, so the thing to do is to fix what’s broken with your room as opposed to try and make a fantastic room.

Things like bass trapping, you don’t have to tune the room for bass trapping. Just break up the corners. You know, lean a mattress up in a corner and see if that makes it sound better, and if it does, build something that’s kind of like a mattress but looks better. There are really easy tricks about when you setup your speakers if you’re in a small rectangular room, first of all, don’t setup straight in the room, try going diagonally, and that will break things up.

Get somebody to hold a mirror on the wall, and when you can see your speaker, you’ve just found the first reflection off the wall. Just put carpet on there. You don’t have to get a really expensive set of things. I mean, there’s some amazing products out there, which would work better than just hanging up a packing blanket, but you can do a lot by hanging up a packing blanket. Just cutting down on first reflections, fix the worst of the problems, and just make it so it’s fun to listen to music, and then you’re good. Then just learn your room. I think there are also a lot of people who will spend a lot of time treating a room, and not think about the fact that they have speakers that sound terrible.

Get good sounding speakers and then you can actually hear what’s going on.

Mitch: Right, right. So you mentioned having fun listening to music, and we’ve kind of been dancing around the issue of sound quality, and the reason that Mojave Audio and Royer Labs brought you in here was for a presentation called Lost in Translation. Tell us what that’s about.

Andrew: Basically what it’s about is I realized about two and a half years ago that as an engineer and a producer and a mixer, I didn’t have a really good handle on what would happen when I was done with a record. So I know everything about making records. Well, certainly not everything, but I know a lot about making records, but I knew nothing about the ecosystem involved in my record making it to someone’s computer through iTunes, or Amazon, or streaming through Pandora, or Spotify, and what it sounded like, what the actual file formats were, what conversion process they used, did they do any mastering before hand? Was it a single step encoder or a dual step encoder? All of this stuff that we sort of kind of know about, but not really, and I decided I wanted to really know about it, and when I did realize, “I need to tell people this,” because it’s actually really important.

It’s so easy to make a record, and you think it sounds awesome, and then go, “Great, that’s done. Let’s send it off out into the universe,” and very few people who make records actually go buy their own records to see what they sound like. People don’t spend the time to upload their own music to YouTube so they can control what is being encoded to the formats that most people listen to music, so it was a way of sort of quantifying it, and originally, the Recording Academy, NARAS, sponsored me to do the talk, and then since then, I mean, getting Dusty and John at Mojave and Royer to bring me out here to do that was — I mean, it’s amazing, because it feels like — it’s a message that people understand that everybody should hear, so you start thinking about what it is you’re listening to, and the fact that they’re manufacturers who have nothing to do with consumer audio distribution, saying, “You know what? We need you to go tell this group of people, and we need you to go tell this group of people.”

It’s a great step forward I think in making people sort of appreciate music, and appreciate audio quality as having something to do with the art of music, which of course is what music is all about.

Mitch: Right, right. Now, it’s like, an hour long presentation or more, and you play examples, and it’s very revealing when you hear some of the differences and things, but for people watching the video, is there something we can do as music creators to get a better result in the end? Aside from educating ourselves on this?

Andrew: Well, I mean obviously, making your record sound as good as you can helps, but this is not really an issue about audio file mixing in the, “I want to win a Grammy for my engineering” way, it’s more about, however I’ve decided my record is great and done, and ready to go out into the world, how do I make sure that is translated in the best way to the people who are actually going to listen to the record?

So in that case, Apple has published a great white paper about how to master for iTunes, and they have a whole program, Mastered for iTunes, so having 24-bit source files delivered to Apple instead of 16-bit, giving the encoders half a dB of headroom will give you a lot less distortion on a loud mix than if you just give it a full scale mix, and this doesn’t mean don’t limit it, it just means you can take your limited brick wall mix, and turn it down half a dB and encode it, and it will sound better than if you don’t.

So there are some pretty specific guidelines, but I think most of it is just being aware of the fact that all of these services sound different, and that all of these services are based on content delivery, not on music listening experience, and as consumers, going back to these companies, and saying, “Man, your stuff sounds terrible, and I am no longer going to subscribe,” or, “I’m going to stay a subscriber, because I love your service,” but write a letter to say, “Please make this sound better.” You know, this stuff sounds bad.

So hopefully, there’ll be sort of a — not a grassroots movement, but the consumers will be educated, because anybody who makes records for a living is also a consumer, and we’re the most informed consumers there are, yet very few of us actually know what’s going on. So it’s just an attempt to educate and give context, so that the next time you listen to XM Radio, you realize what bit rate that is, and why it might not be the best sounding place to showcase your record.

Mitch: Yeah, sure. Sure. I think there’s increased awareness right now, because Neil Young has his player coming out, the high resolution, Pono, right? The high resolution player, and there’s a lot of buzz about that. It’ll be interesting to see if that really catches on in a broad sense.

Andrew: Yeah, exactly. I mean, I think it has potential to catch on as a product itself, but hopefully, what it really does, is it makes just regular folks who buy music think about, “Oh, there’s more than one option for how I listen to this, and maybe Pono isn’t the one I want, but I actually want to go after finding a CD, which is getting more and more difficult,” or going back to vinyl or something, but not just sort of taking whatever you can get, and saying, “Well, that’s all there is.”

Mitch: Right, right. So you kind of came up with the classic route. You went to recording school, or studied recording in school, the worked your way up a few different ways. The industry has changed so much. What advice do you have for someone who wants to get into being a mixer or wants to work in the music production area?

Andrew: Run away. No, I’m kidding. But I would say that there used to sort of be a myth in the music industry that it was like playing the lottery, but the odds are pretty good. You could toil away, not make much money, then all of a sudden, you’d be a gazillionaire, and be on MTV Cribs, nobody is becoming a gazillionaire, so the first thing is make sure that it’s your passion and you love it, because otherwise, you really shouldn’t do it. Do it as a hobby. You know, there’s plenty you can do in your spare time, but if you love it and it’s really what you want to do, I think at this point, it’s very hard to find a mentoring way into the industry, you know, there are very few studios you can be a runner at, and then be an assistant, and work your way up, so I think if you just start doing it, that’s the best way to do it.

The best way to learn how to record a band is to record a band. So now, especially through you guys, it’s easy, and not that expensive to get a decent sounding setup with a few microphones, get yourself a couple of Royers, a couple of Mojaves, set them up with your laptop, and start recording bands, and learn about acoustics, and learn about electronics, and learn about all the stuff, because I think the one thing — and this has always been the case, is that recording is very technical, and it involves a lot of physics, it involves acoustics, it involves electronics, now it involves computers and digital audio theory, so there’s a lot of technical stuff you need to know, but that technical stuff should be just a given so that it’s at the service of your art and the creative process.

So just read as much as you can, read interviews with other people, I mean, interviews with me are useless, but interviews with other people are awesome. I mean, you can sit down and read ten pages of what Tchad Blake thinks about something, and what Manny Marroquin thinks about something. You’ll learn just as much from that — watch Pensado’s Place. Brilliant, absolutely brilliant, actually sit down for an hour with someone as just intense and invested in the art of making records as Dave is, and the questions he will ask, like, “What about the reverb on that thing in the third verse of that song on beat four,” and you’re like, “What?”

Then you go back and deconstruct your own process, so I think just as much as you can learn and be exposed to people who have been doing it longer than you, just do it, because that’s as close as you’ll get to being able to sit in the back of the room and be yelled at by an engineer.

Mitch: Great advice, great advice.

Thanks for coming in today. The presentation was awesome, so much value to that. I mean, like you said, what we’re doing is creating art, and so getting it out there with the best possible quality is of a fair amount of importance. That’s very cool you’re doing that, so we really appreciate it. It was great seeing you.

Andrew: Yup. Awesome, thanks for having me. Alright.

Mitch: I’m Mitch Gallagher, thanks for joining me for the Sweetwater Minute.

Andrew: He’s Mitch Gallagher.

Mitch: It’s true. [laughs]