6 Tips for Using Reference Tracks

Article Content

It’s a daunting challenge to recreate the energy, fidelity and emotion of commercially successful music releases. I find that an essential technique to employ during this pursuit is to use reference tracks while producing, mixing and mastering. Here are some of the best practices when using reference tracks during music production.

1. Ask the Artist

I have my own thorough (and constantly growing) list of reference tracks that I use during producing, mixing and mastering, but it’s often more helpful to understand exactly what the artist is going after. Ask the artist to provide several examples of music that could be used as a sonic roadmap during your own process.

I also find it helpful to ask them why they chose their references, and what specifically they like about the particular pieces of music they’ve provided me. This establishes a creative dialog between you and the client, and I find that open communication is essential when working with artists. At the very least, I expose myself to some new music.

2. Micro vs Macro

When using reference tracks, it’s great to listen to them a couple of different ways. When taking a macro approach, I step back from smaller details and listen to the broader sonic brushstrokes — is the overall mix bright and clear? Perhaps a production is carried by an individual part of the arrangement, say vocals or drums, in which case these parts may be a lot louder than the others. Is it apparent that there’s a lot of compression and limiting on the master? Or did they try to keep everything sounding more organic and detailed? Are a lot of elements drenched in reverb and delay, or are they bone-dry? I’ll listen to these big-picture details and then compare to what I’m working with.

In the micro approach, I listen much more critically. I use my ears as sonic microscopes in an effort to perceive the smallest details. Microscopes —“micro” — get it? I’ll listen to the finest nuances, for example, not only how loud the kick drum is in relation to everything else, but how the kick drum has been processed. How much room sound does the kick have? Does it sound like it’s been augmented with a sample? I’ll repeat this critical listening process when analyzing virtually every element of the arrangement.

I see this opinion shared all the time; “If you record it right initially, you shouldn’t need to process it later” and I’ll save a long rant for another article, but not only is that sentiment generally used non-constructively, it also discounts a lot of the creative work that mix engineers and producers are hired to do in the first place.

If the vocal is silky smooth in my reference track, and that quality is lacking in the production I’m working on, I might immediately think about adding some 10 or 12k with a Pultec-style EQ. If my reference track has a blistering fuzzed-out guitar, I try to determine how that distortion was achieved. It could’ve been achieved by a pedal, a guitar amp or even an overdriven preamplifier. I then reach into my toolbox and try to achieve that color. I listen to each part and determine if they’ve been compressed, saturated, or run through reverb and delay etc.

I’m certainly not going to say to the client “I can make it sound that way, but if you had recorded it right the first time, I wouldn’t have to change a thing,” I’m going to use all of the tools at my disposal to achieve the artists’ creative vision, and often times, that vision was informed by another piece of music, if not several. I use each and every element of my references when making creative decisions about what to do in my own work.

3. Do Some Research

Listening to reference tracks is great, but conducting research is often more educational than what your ears alone can tell you. When “Brothers” by The Black Keys came out, I knew it was going to be a sonically influential work of art. Obviously, the music is great, but it’s a unique-sounding album. With its wild-yet-appropriate saturation, expressive slap delays and a defined sense of space and tone for each instrument and voice, I knew indie artists would be after this “old-but-new” sound.

Fortunately, a really insightful interview (which I can’t seem to be able to find as of late … sorry) with Mix Engineer Tchad Blake came out shortly after the album release. It was extremely insightful, with Tchad speaking about his process, mixing philosophy and even specific plugins that he used during mixing the album. There are certain techniques I probably wouldn’t have tried had I simply listened to that album as a reference, and so getting information directly from the source was even more helpful.

There’s obviously a wealth of information online found on blogs such as this one, but magazines, scholarly articles and books are also invaluable tools in figuring out how professionals achieve the sounds they do, and isn’t that essentially what we’re doing by using reference tracks in the first place?

4. Listen Everywhere

When employing my macro and micro approaches of comparing my productions to commercial releases, I make sure to listen to both in as many listening environments/configurations as possible. This includes but isn’t limited to:

- Main monitors (with sub)

- Main monitors (without sub)

- Sub only (to hear what’s really happening down there)

- I turn the volume way up, step out of my room and listen to how music sounds throughout my house

- Multiple sets of headphones

- iMac speakers

- Airplayed to my home stereo system

- Car

- Phone

- Two sets of large, high-quality monitors at a studio

There’s more, but if my productions hold up to commercial releases on those aforementioned configurations, I’m in pretty good shape. I really love listening out of my phone to get an idea of balance on commercial releases, and that’s perhaps the only thing I love about listening out of my phone.

5. (Seeming to directly contradict my previous point) Don’t Obsess

Face it, some of the productions we work on simply aren’t written, performed and recorded with the level of care and talent that commercial releases are afforded. While it’s great to use reference tracks to orient yourself to a listening environment and to provide a sonic roadmap for your own work, it can also be frustrating and counterproductive to obsess over getting your productions to a level that they simply can’t reach, and in some cases not through any fault of your own.

An example — I worked with a band long ago that was absolutely fixated on getting their tracks (especially the drums) to sound like a particular (and well known) artist. The main problem was that the drummer just wasn’t very good … not only that, the drums were recorded with a minimal number of microphones, in a less-than-great room.

The issues of how they were tracked I can sort of fix with samples and processing, but there’s simply no substitute for a solid drummer playing with great feeling. I kindly told the band that I’d probably never be able to exactly replicate the size and clarity of the drums in their reference because of the low-budget way in which their own were tracked, not because their drummer was sloppy.

Additionally, I’m often not after cookie-cutter sounds in my productions. I want to create music that feels familiar but new, and sometimes obsessing on having each and every part to match the reference simply doesn’t serve the song or the artist. If the artist desperately wants that sound, then fine, but I never forget to follow my own intuition rather than the exact sonics of a reference.

6. Use the Tools

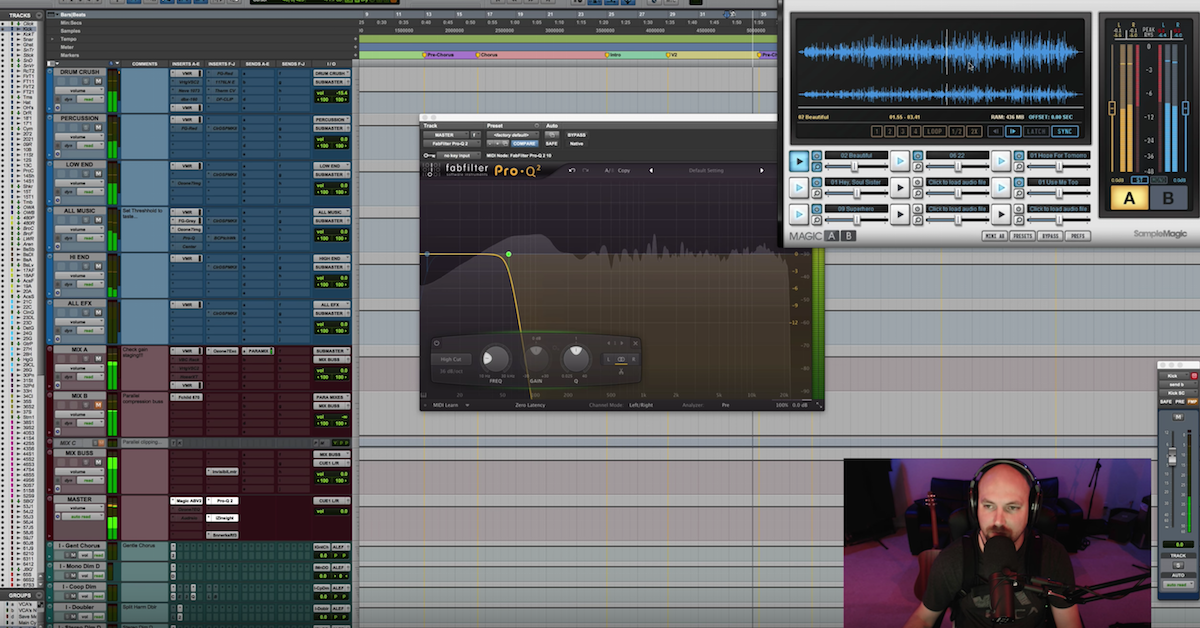

There are some absolutely stunning plugins out there for getting your productions to stack up to the quality of successful releases. iZotope, FabFilter, and plenty of others make software that aid you in the pursuit of matching your work to commercial standards. My favorites are the trio of plugins from Mastering the Mix: EXPOSE, LEVELS and REFERENCE.

Both EXPOSE and LEVELS are fantastic metering/informational tools that show how my mixes and masters compare to modern standards.

REFERENCE actually allows you to load in tracks and A/B, Level Match, and gather loads of valuable information about how your productions compare to your references. My favorite tool is being able to solo the low, mid, and high frequencies and analyze how my work differs from my own favorite reference tracks.

Your ears, of course, are the most valuable tools when using reference tracks, but don’t discount the great technology we are fortunate to have at our fingertips.