The Complete Guide to Mixing Low End

Article Content

Bass. Kick. Sub synths. 808s: All of the things that make music great. And yes, even you, coffee shop open-mic lady with your ukulele, would benefit from some 808s. I will die on that hill. So let’s talk about it.

The Low End is the anchor to our record. It provides the fullness and power to make a record sound big, and it gives physical energy to the groove. The Low End is the part of the record that we actually feel, not just hear. However, it can be a bit of a trick to get right.

Acoustic Properties

If you struggle to get the low end of your record right, you’re not alone! The nature of low-frequency sound tends to be more difficult than the midrange and treble.

The first issue is that we don’t perceive bass as loudly as we perceive midrange frequencies. A bass tone played at equal amplitude as a midrange tone will be perceived as quieter, even though the energy of both tones is the same. This means that we need to mix bass louder in order to hear it as being balanced. In order to get the bass to be truly massive sounding, we are fighting against our own natural hearing!

The second issue is that low acoustic waves are harder to work with in a space. The physical length of bass waves create more dramatic modal interaction within a room. In other words, standing waves are going to mess up our bass frequencies, creating uneven peaks and dips. It’s not uncommon to see 18 dB nulls in an untreated room. That can really mess up our listening accuracy.

It’s also more difficult to get rid of these problems. Because bass waves are so long, they require more depth of absorption to mitigate. Proper bass treatment requires about four feet of depth! The only other option is some kind of bass trap, and unfortunately, those are expensive, and generally tuned to specific narrow ranges of frequencies.

In other words, bass requires more dynamic range and is harder to hear accurately than other stuff. So if you’re struggling — don’t get down on yourself.

Be Proactive and Get Your Monitoring Right

I’m going to start this by saying the easiest way you’re going to improve your low end is by getting your monitoring position right, and by calibrating your sub correctly. Hiring an acoustic specialist is by far the easiest way to get this right. There are also DIY guides to shooting your room and using SPL meters, and honestly, if you are very specifically looking to engineer, getting a technical calibration is best.

Even doing it with a company like Sonarworks is a better solution than just winging it.

However, let’s say you’re not budgeted for any of that — you can use music you like. Get a playlist together of music that you really dig the low end on. Start by getting your nearfields in the right spot. If your listening space isn’t huge, you’re gonna have to get right up against the wall. Somewhere between flat to the wall and a foot and a half away is going to be a sweet spot where the bass seems to come into focus. Have a couple of friends move your speakers an inch off the wall at a time and mark anywhere the bass sounds very clear and the punch of the kick in your playlist becomes very defined. You want to be at one of these points.

When getting your sub right, again, you can do this with a playlist. Set your sub crossover to 80 Hz. You can set the sub-level based on what you like to hear — as this is what you are going to mix to. From there you want to move the sub around until the deep lows come into focus, and again, mark those spots!

Now it’s time to play with the crossover. The idea of a subwoofer is to support your primary monitors, not to do their job! 80 Hz is pretty standard, but every set of nearfields is a little different. Generally speaking, you want to find the lowest frequency your nearfields are spec’d to reproduce, and go just a hair above that number.

For example, I have PMC TB2S+ nearfields. They are spec’d to 40 Hz, so with a subwoofer, I’d probably want to set the crossover to about 50 Hz give or take. Of course, we ultimately determine this by setting the crossover in various places and determining what sounds best to our ear.

Once we have our positioning and calibrations correct we can help things along with room treatment.

I’m going to assume that most people reading this don’t have four feet of room depth to pad up with loose insulation. I sure don’t. If you do, go for it.

Now, superficial absorption can help a lot when it comes to the 100 Hz and above. Six-inch deep, dense insulation panels (like Owens Corning 703) with a two-inch air gap is very effective and requires much less real estate. Unfortunately, it gets much less effective when we’re talking about stuff that’s under 100 Hz.

I still recommend doing at least some degree of treatment using acoustic panels. Even if we can clear up the 150 to 400 Hz range, that’s still going to make managing the bass a lot easier, as a lot of our bass content spills into the lower mids. Most of our bass content is actually between 80 to 250 Hz, so we can get a good amount of it tightened up with superficial absorption.

By the way, this is not audio mysticism. I’ve set up studios many, many times and the difference that getting your positioning and room acoustics right makes is absolutely tremendous.

Now the Fun Stuff

Let’s talk about the actual mixing process. The secret to understanding mixing, of anything, is to know your goals. Before we dissect how to do something, we have to first be specific about what we want to do.

I’m going to do something I try hard not to do and oversimplify things a bit. In general, our goals for low end falls into two camps: the Big Clean Clear Punchy camp, and the Live Gluey Organic camp. And maybe sometimes we pull some ideas and techniques from one camp and adapt them to the other.

Let’s talk big, clean, clear, and punchy first because I think our goals are pretty straightforward here. We’re going to want these qualities from a lot of our Pop, Hip Hop, and EDM records, as well as related genres.

Our goal here is going to be maximizing our “sonic real estate.” We want to focus each element of our low end into its primary living space while keeping them out of the others. For example, let’s say we have a low piano, a kick, and a synth bass. All three of these elements are going to have frequency content that spans from the low bass range well up through the low mids.

Unmasking Elements

Each of these elements on their own sound big, but when they play together, they all become a bit smaller. This is because each element is covering up some other part of the other element. We can reduce this effect with EQ. We can assign importance to where each element is living and clear up that space for them.

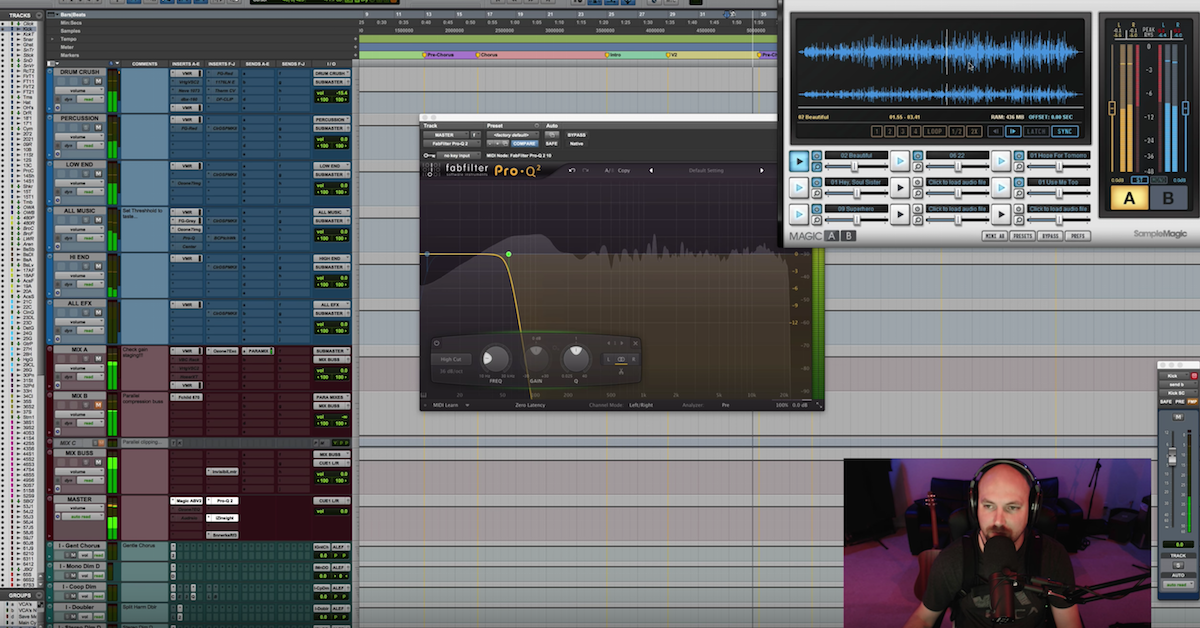

For example, we may decide that it’s more important for the synth bass to dominate the 80-120 Hz range, so we EQ and attenuate that range on the low piano. Effectively we cut that bit out of the piano so that the synth bass can really shine there. On its own, this might take some power away from the low piano, but when played along with the synth bass, we don’t miss that power because the synth bass is supplying it.

Now let’s say the synth bass has an overdriven quality to it, giving it a lot of body around 200-500 Hz. Played along with the low piano, this may sound very muddy. So we have to make a decision — which is more important musically for the song? Is the piano providing the support for our main melody or is the bass? In choosing what’s more important we decide that either the bass really just needs to provide the power for the record and we attenuate the low mids out a bit, or, maybe the piano is just meant to add color, so it’s the piano that loses out again and gets that low mid cut.

Whatever we decide is the dominant element, we preserve, and whatever is there for support, we shift out of the way until the dominant element really pops through.

What about the kick?

The kick is a tricky element because not only is it a low-frequency element, but it’s also a very dynamic element. So it ends up taking up a lot of space. I’m going to go more in-depth on contouring the element itself, but for now, I just want to talk about making space for it.

Again, we need to make a decision about who is holding down the low end rhythm: the bass, or the kick. Traditionally we assume the kick, but there’s actually a lot of styles where the bass is really the important character and the kick is there for accent. Jazz, Old School Funk, many styles of Rock, Highlife music (… it’s a fairly extensive list.)

So don’t just assume the kick is going to dominate that range. Also, it’s important to recognize that sometimes the kick and bass already get along really well, and it’s not important to make space for the kick.

All that said, it’s fairly common where we do end up having to kind of make room down there, so here are a few things that can really help.

- Low-shelf sub out of the bass guitar. Mic’d bass cab, in particular, will tend to carry a little extra emphasis on the sub tones, especially if the bass player happens to be hanging out on the low string. A smooth shelf from around 30 Hz (depending on how broad the Q) can help the low end breathe so the kick can really rattle the speakers.

- Don’t be afraid to be heavy-handed with acoustic kicks. Conventional mic techniques for acoustic kicks often don’t carry a crazy sub-tone. In general, if we want a tight, punchy kick sound we may be boosting a LOT of top-end to emphasize the batter, doing a pretty significant tight dip or two in the mids to get the room-n-bloom out of there, and adding anything from a narrow bell boost to a low shelf to get that sub. If we don’t necessarily want sub, because the bass part is already there, we may be looking at the primary bass range from 80 to 100 Hz to pull up the weight of the kick. And again, we might be making pretty dramatic moves. For context, it’s pretty common for me to turn the top end of an SSL-style EQ all the way to the right to get the attack I want. And on that note …

- The attack is what gets the ear. The easiest way to get a kick to stand out is to add top end, not bottom. However, we don’t always want a clicky kick. If we want the kick to stay darker, but need it to cut, we may need to set up some kind of a ducking chain. I like broadband ducking — that is, putting a compressor on the bass but keying the sidechain detector of that compressor to the kick. I use a very fast attack and release and use the threshold to control how much of the kick I want to poke, and how much of the bass I’m willing to lose. A lot of engineers like to use band-specific ducking with multiband compressors or Wavesfactory Trackspacer. These can be very effective, but frequently don’t unmask the kick as well. So it really depends on how subtle we need to be.

Now Let’s Talk Live, Organic and Gluey

In this scenario, we want the bass elements to run together to create a pillowy bed.

A very common example of this is in a lot of Rock genres. The low end of the rhythm guitars is meant to blend in with the bass as if they’re all one big guitar. Here, separation is our enemy, not our friend. In this way, we have to completely flip our mindset.

Watch out for tracking that’s too clean. This is very very common. Bands will often come into a studio without a producer and without a specific sonic vision. Engineers generally will (and should) default to tracking things as cleanly and clearly as possible, knowing that things can always be dirtied up later if need be. Many producers will adopt this approach as well: catch it clean and decide later.

Personally, I like to capture things as they are intended and follow through with the vision from point A to Z. But that’s a whole other topic. Another common example is when the bass is strictly DI’d with no amp. There are a few DIs that have great tone, but a lot of them are very very clean.

The solution is to get your distortions in order. Whether it’s plugins, hardware, or re-amping, you’re going to want some mojo that extends the bass into the upper octaves a bit.

With the kick drum, we may want to flip things as well. All that stuff we take out of the acoustic kick in the low mids to make it tight and punchy — that’s the shell tone, room tone, and head material giving the kick its texture and personality. If we want something organic sounding, that’s exactly what we don’t want to remove.

Here’s a great technique:

Send the drums and bass to the same bus. On that bus, put your favorite saturation plugin. I like the PA BlackBox HG-2 for this. Saturate everything together, it’s a great way to get gooey and gluey. A little compression can help as well. Nothing dramatic, just medium release, medium attack.

Let’s Talk Specific Elements!

In this next segment, I think it would be really cool if I could share some of my personal techniques and approaches to specific, common elements: Kick, Bass Guitar, and 808s.

Kick Drum

I mentioned a few of my kick techniques a little earlier but now I’m going to dive a bit more in-depth.

First, I want to discuss acoustic kicks — kicks directly from a mic’d kick drum.

First and absolutely foremost — if we have multiple mics on a kit, we need to make sure our mics are in phase. If I have more than one capture on the kick itself (like a Kick In and a Kick Out), I will buss them all together to one group channel. From there I pick my primary kick mic, and that’s usually the one with the best texture. I then bring in secondary mics, one at a time, and invert the polarity. This should give us dramatically different results — one should sound like the low end is big and bold, and the other should feel like the kick is being high-passed.

Obviously, we want the one that has the big bold low end. I then place a polarity inversion plugin on the group bus itself and bring up the drum kit overhead mics and flip the phase on the kick group and listen for what gels with the overheads better.

Once I have the phase relationships right it’s time to set up a noise gate. My favorite gate is the Sound Radix Drum Leveler. The accuracy and degree of customization is ridiculous. I will set this up on the kick captures themselves, not on the group, because different captures will have different levels of bleed.

My goal with my gates is not to eliminate bleed completely. If our goal is a live, organic feel, we actually want that bleed, but even if we are going for clean and clear, we need to preserve the sustain of kick — so over-gating is not the move. The gates are really there for controlling the amount of bleed we are getting, particularly once we add compression to our kicks. The more compression we add, the louder that bleed will become, so we can use those gates to control that.

In regards to compression — there are a million ways to compress a kick drum. And it always depends on the initial sound of the kick. 1176 or Distressor are great for reigning in transients while making the overall sound punchier. The dbx160 is a classic for giving a kick drum some snap. Other compressors like an LA-2A, LA-3A, or dbx165 in overeasy mode are great for rounding out kicks and making them “boofy.”

It all comes down to what the kick wants. But no matter what, an acoustically recorded kick drum usually wants a pretty heavy hand. In solo, it can easily sound like you are over-compressing the close capture, but in the context of the complete drum kit, heavy compression on the close kicks usually sounds good as it blends with the natural sound of the overheads and rooms.

For sampled or programmed drums, my biggest tip is: do nothing.

If I can leave a kick completely unprocessed I usually feel pretty good about it. Samples tend to already be heavily processed, and for most sample-based music, the low end is being built around the kick. That said, sometimes a sample needs a little love. A bit more low end or top end can be required, and a bit of light clipping can actually push a drum a bit further. Mind you, many sample pack producers already clip drums to get them louder, so don’t just go clipping anything. This can also work really well on acoustic kicks, but be careful because distortion can mess with the phase, so don’t forget to check your phase to your overheads when doing this. Soundtoys Decapitator and the Digidesign AIR Lo-Fi are my choices for clipping kicks.

And back to the subject of phase — if your record has layered kick drum samples in it, check the phase relationship. Even though they are not from the same recording you may notice a pretty significant difference once that polarity button is pressed!

Bass Guitar

A lot of bass happens at the source. The overall character of the bass is pretty integral to the sound of the guitar and the player’s style. But there are a couple of things we can do in the mix to really cement the sound that’s present.

If there’s a combo of both DI and mic’d amp, make sure they’re in phase. This may require manual time alignment or using a plugin like Sound Radix Auto-Align. Personally, I try not to rely on the DI too much, I prefer to get my sound from the amp. However, the DI can be useful for locking down a clean and clear low end. Sometimes brick-solid compression on the DI tucked into the mic’d signal can bring a bass capture home, almost like a parallel compression technique.

Now let’s say we have no DI, just the mic. Even a well-played bass tends to be either slightly too bouncy without enough weight or too heavy without enough attack. An 1176 with a slow attack and a medium release is great for putting a little attack and punch on the bass. Similarly, a medium to fast attack is good for solidifying it.

We can also use multiband dynamic processing to take this idea further. We can use fast attack compression on the low band — the stuff under 200 Hz — to make the low end really consistent. We can then use upward expansion in our upper band to exaggerate the attack. This is a great way of having our cake and eating it too — a heavy yet punchy bass line.

Ok, but what if we only have the DI. My first inclination would be to re-amp it through a cab. If that’s not an option, my goal is to get the one thing DI’s tend to miss: character. Drive, distortion, fuzz, auto-wah, whatever speaks up and produces those precious overtones. I’m a big fan of Native Instruments Guitar Rig. We can get all sorts of great flavors and distortions mixed up on that otherwise clean signal.

808s

Speaking of overtones, that’s kinda the key component to what makes an 808 really sing. Without all the stuff happening above the fundamental, an 808 is essentially a sine wave with some detune. Now, throw in some drive and some texture, and we’ve got something worth writing home about.

Very, very often, I leave 808s as is. They just kinda are what they are. Sometimes I want to expose their personality a bit more. I actually did a video a few years back on The Pro Audio Files YouTube channel (which you should absolutely be subscribed to!) on the subject. It’s a demonstration of how I will bring up the low midrange on a multiband compressor. That’s where all the fun harmonics in the 808 live. It’s also where the punch lives. I use a multiband comp so that I can keep the punch in check.

If I don’t like the tone of the 808, sometimes I’ll low-pass it and impart my own distortions. I’m a big fan of iZotope Trash for this. There’s no right or wrong, it’s just about getting the appropriate feel for the record. Sometimes we want a buzzy or grungy 808, sometimes we want something a little smoother and boofier.

I also like to stretch my 808s across the stereo field from time to time. iZotope Trash is good for this as well because the convolution module of the plugin has a stereoizer that works well. Or, if I’m retaining the 808, something like iZotope Ozone Imager is good. This imager is multiband so I can spread the low end and midrange differently. Sometimes I want the mids to stay really punchy and just spread the lows a bit. Sometimes I want the mids good and wide. I usually don’t spread the lows too much because it will get pretty phasey pretty quick, but a little spread can be good.

The real trick is getting the 808 to work with the kick drum, and guess what we check for that: yup, phase.

The phase relationship between the kick and 808 pretty much defines whether or not they will work together. Because the 808 moves notes, the phase relationships will change. So I check every kick against every note of the 808 in a loop and invert the polarity of every kick that needs it. Once I’ve got a complete loop worked out, it’s copy & paste time.

One thing that will really mess up an 808 is when the tail duration runs into the next note. This is common with sequenced 808s. One note runs over the next and muddies things up. Unfortunately, there is no real way to fix this in the mix, it’s gotta be played/programmed right from the start.

I sort of look at synth basses the same way I look at 808s. I’m either leaving them alone or bringing out their character and sometimes widening them. The only difference is I might trigger some kind of a ducking process to open up space for the kick.

Lastly …

Listen to your bass at different playback levels. If we listen quietly, we’ll hear if the bass has enough midrange to it. This is connected to the acoustic response of the human ear. If we listen at a conversational level, we’ll get a solid impression of the lows and subs. You also need to know your monitors a little bit. Typically if you can feel the sub on small nearfields at a conversational level, it’s too much. Bigger nearfields, mains, or speaker systems with a dedicated sub will tell a different story. For those, you probably want to feel the subs to some extent even at a modest playback (and certainly if you turn them up).

Low end is tricky, but with decent acoustics and a little practice, it’s not nearly as daunting as it first appears.