5 Common Drum Programming Mistakes

Article Content

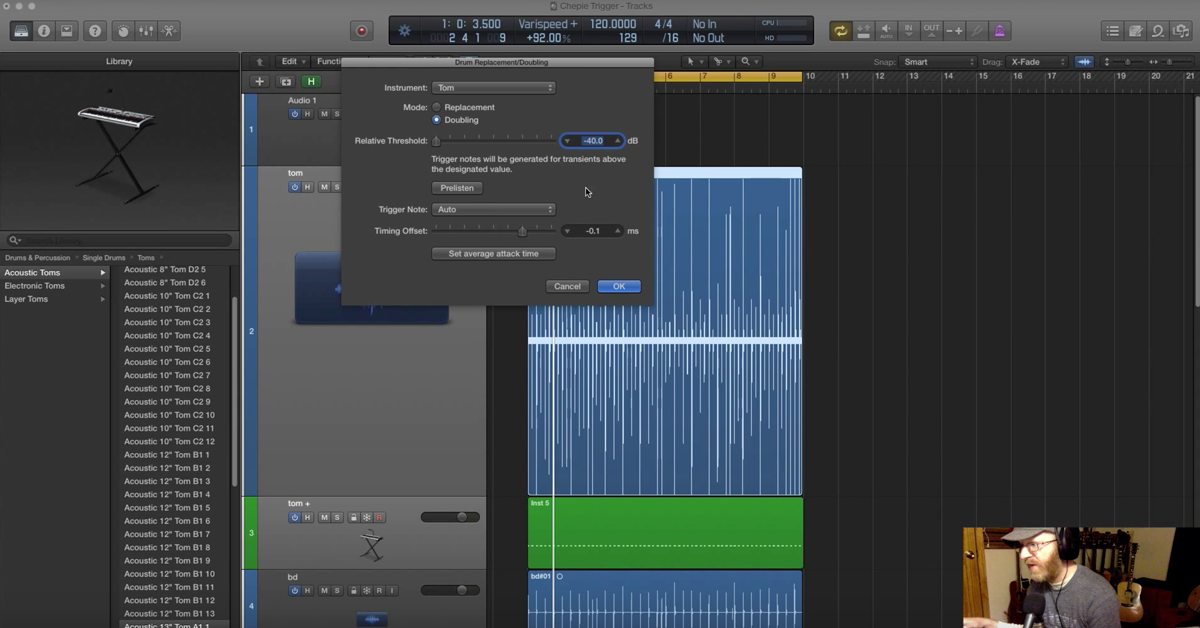

With all of the amazing sampled acoustic drum libraries available on the market nowadays, programming parts that sound almost as good as the real thing is now more viable than ever.

This being said, unless you’re able to inject some humanization into the parts you write, chances are you may end up with lifeless, robotic sounding drums.

On that note, today we’re looking at five reasons why your programmed drums might not sound the way you want them to.

1. They’re Unrealistic

Unfortunately, drummers are limited to having two arms and two legs, meaning the maximum number of individual kit pieces they can hit simultaneously is hard-capped at four. Not only that, but the fact that a drummer’s legs only have access to the kick(s) and hi-hat pedal means that the maximum number of other shells & cymbals that can be hit simultaneously is reduced to two.

Keeping this in mind while programming drum parts is important if you’re looking to produce realistic results. Writing parts that would require the drummer to grow an extra limb or two will deal a huge blow to how believable they are straight off the bat.

Although technically there’s no rule saying you’re not allowed to layer multiple drums to achieve the sound in your head, the second you do, you’re compromising the “performability” of said parts in the live domain later on.

Here’s an audio example to demonstrate my point:

The beat in the first four bars is akin to something a real drummer could play, while the second beat in the following four bars would be physically impossible to play in real life because of the dual tom and cymbal crashes overlapping.

2. They Lack Dynamics

Dynamics, or a lack thereof, is the #1 reason a lot of programmed drum parts end up sounding fake and “machine gun-like”.

Let’s take a quick look at a few major mistakes people tend to make in this aspect:

Using Max Velocity For Every Hit

When sample libraries are recorded, the highest velocity hits (127) are often the result of the drummer being told to hit the drums/cymbals as hard as they physically can. The thing is, when drummers actually play, they very rarely go all-out and hit everything at full-force. This being the case, with most libraries, the samples which are one or two layers below the highest velocity hits (around the 110-120 range) are actually much closer to what you would expect to hear from a real drummer sitting behind a kit.

Before writing your next beat, take the time to determine which sample layer sounds best with the particular drum software you’re using. Making this simple switch alone will go a long way towards making your drums sound much more realistic.

Here’s an example of how applying dynamics can transform a programmed drum performance:

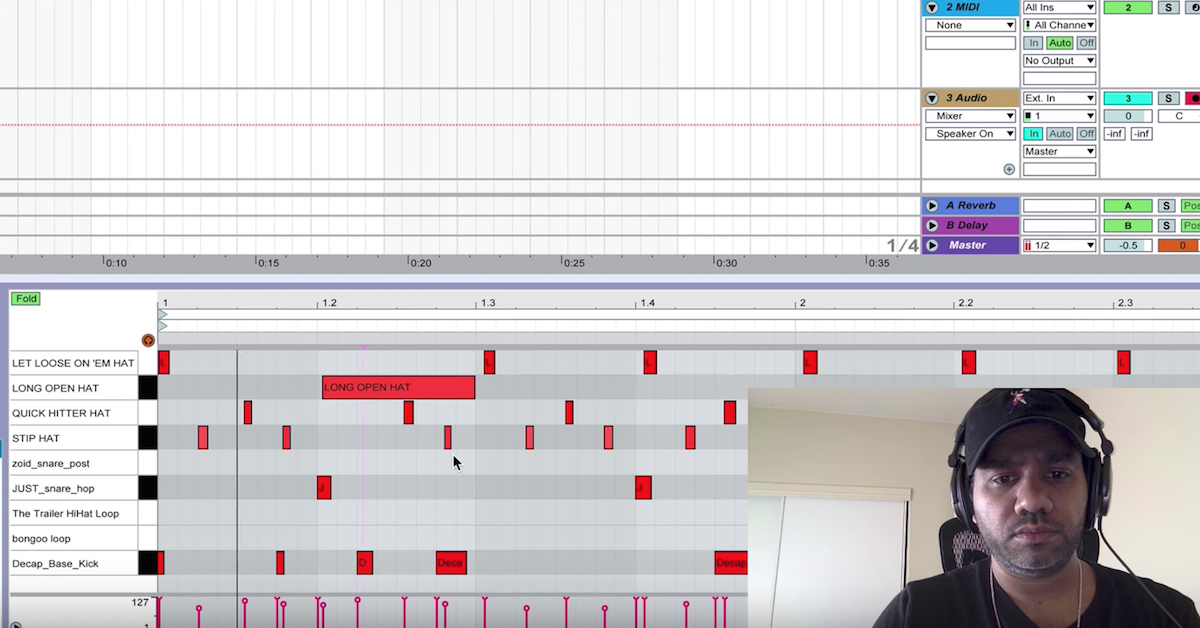

Lack Of Accents

A common mistake when programming hi-hats, rides and fills is to use the same velocity for every single hit, which results in usable, but bland beats which don’t really offer much in the form of groove or interest. This is where accents come into play.

As the name suggests, an accented note is one which has been accentuated, or in layman’s terms, hit harder compared to the rest. By simply changing where your accents fall, you can transform your drum beat into something totally new without having to add or remove a single note.

Check out the following 3-bar example, which demonstrates how simply changing where the accents fall in an 8th note hi-hat pattern can change the overall feel and intention of a beat:

In the first bar, the hi-hat is accentuating every eighth note. In the second bar, the hi-hat is accentuating the quarter-notes. In the third bar, the hi-hat is accentuating the eighth note “&’s” which fall between each quarter note.

Another detail to keep in mind is the discrepancies between left and right hand/foot hits. Depending on whether a drummer is left handed or right handed, they’ll often have the tendency to hit slightly harder with their dominant side. Keeping this in mind while programming quick, successive notes in drum fills can go a long way towards improving realism and preventing them from sounding too fake.

3. They Don’t Serve the Song

One of, if not the most important question you should be asking yourself regularly throughout the music production process is “What does the song actually call for”?

It’s simple — if you have a soft, slow-tempo, balladesque track, but you go in and program some complex, progressive, blistering 32nd note drum fills which are flying around the kit at lightspeed, the resulting product won’t make musical sense.

Your primary goal when writing drum parts is to drive the song forward in the most effective and musically cohesive manner — not to write the most technically impressive, fancy parts you possibly can just for the sake of it.

Progressive metal band Periphery’s “The Bad Thing” is a great example of drum parts which have been designed to perfectly complement the surrounding instrumental arrangement in a totally musical way.

Listen to how the drums, guitars and bass are all locked in tightly, and how drummer Matt Halpern is pretty much mimicking a lot of the guitar riffs exactly through his playing. The result is a kind of “wall of sound” in which everything is working in unison towards the goal of sounding as heavy as physically possible.

4. They Don’t Sound Right for the Context

Much like guitar or bass tones, there is no “one size fits all” when it comes to drum tone.

Rather than me rambling on and trying to explain what I’m talking about in words, I’ll just let you hear what I mean for yourself with a quick analysis of four very distinct drum sounds from four drastically different musical genres:

70’s Pop/Rock: Fleetwood Mac – “Dreams”: Very tight, dry and muffled.

80’s Pop – Phil Collins “In The Air Tonight”: Gated reverb, lots of snare bottom mic/buzz, single-headed, “cannon-like” toms.

Metal – Lamb Of God “Laid To Rest”: Super-clicky kick and shells, ringy snare, quite dry, barely any bottom snare mic being used.

70’s Rock – Led Zeppelin “When The Levee Breaks”: Big, open shells with tons of sustain, huge reverb/room, phaser and delay, quite a dark dark tone overall.

Comparing the examples I’ve posted above, I think you get the point: Choosing the right drum sound for your particular song and musical context is extremely important!

Just for fun, here’s what a metal drum beat sounds like with a genre-suitable sample library in the first four bars, versus how it sounds with a 70’s rock library in the next four bars:

5. They’re the Same From Start to Finish

No one likes a one trick pony. If you’re just blatantly copying/pasting the exact same drum parts each time a section of the song repeats, your listeners are bound to be slightly underwhelmed by the lack of growth, impact and momentum, get bored, and potentially even skip to the next song.

The key to preventing this scenario from occurring lies in expanding on what you started with as the song progresses in order to keep things exciting at all times. In the context of drums, achieving this goal can be as simple as introducing new kit pieces into the mix, switching to double time on the hi-hat or ride, or adding in some additional ghost notes to spice things up a bit, It all just depends on what the song calls for, and what you can get away with.

Here’s an example of how a bare-bones, simple drum beat can be expanded-upon over time:

Conclusion

My best piece of advice if you’re looking to develop your programming skills is to simply listen to your favorite drum songs and attempt to recreate them for yourself via MIDI. With time you’ll start to pick up on what’s going on much more quickly until you’re eventually able to program by sight without even having to hear what you’re doing.

Finally, it’s important to remember that this isn’t a skill which you can master overnight. It takes hours upon hours of practice, experimentation and study to get to the point where you can quickly punch in the beats in your head and have them sounding realistic from the get-go.

Simply program, program, then program some more, and you’re bound to see improvements in no time!

![Fleetwood Mac - Dreams [with lyrics]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/mrZRURcb1cM/hqdefault.jpg)