What Is Knee on a Compressor (+ 3 Mix Scenarios)

Article Content

I recently took a look at how a compressor’s ratio setting affects its behavior and the ways we can use it in music production. In this article, I’m going to be exploring an often misunderstood or simply ignored parameter of dynamic compression: knee.

Let’s start with a quick primer on compression.

Compression Basics

Though compressors come in every color and flavor combination you could imagine, they all share one primary function: reducing dynamic range. Of course, that description sells short the wide range of ways compressors can shape and color the tracks they process. In theory their purpose is simple, but in practice it’s nuanced and versatile.

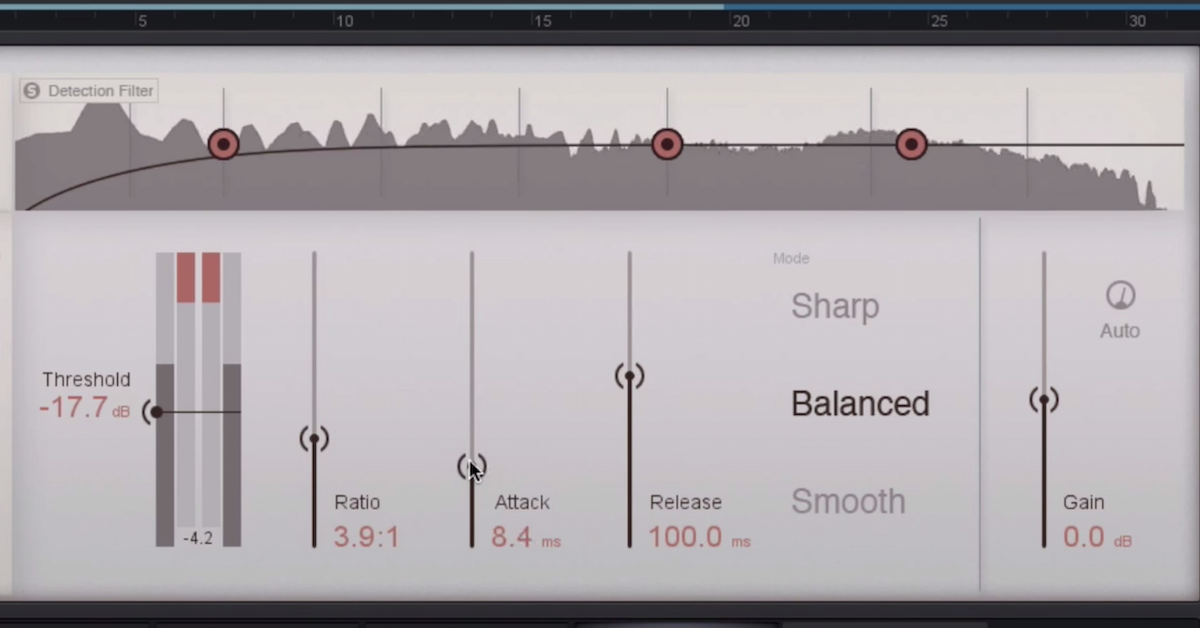

Among the features that help create that versatility are a compressor’s attack and release times, along with the ratio. The attack and release determine the timing of how the compressor reduces the level of incoming signal — potentially dramatically altering the compressor’s sound and behavior — with the ratio determining the intensity of the reduction.

The center of gravity for a compressor’s functioning is its threshold. The threshold establishes the point at which gain reduction “kicks in.” Below it, the compressor leaves incoming signal unaffected; above it, the compressor goes to work. Any of these parameters — attack, release, ratio and threshold — may be user-controllable, or they may be baked into the compressor’s functioning.

What Is Knee About?

If you haven’t read the article on ratio I linked above, and you’re new to compression, now might be a good time to go check that one out. Understanding ratio is a necessary first step for understanding knee. In a sense, knee is about the interaction between a compressor’s threshold and ratio settings.

Though knee is often assigned a numerical value in compressor controls, we tend to describe it more qualitatively: soft, hard or somewhere in between.

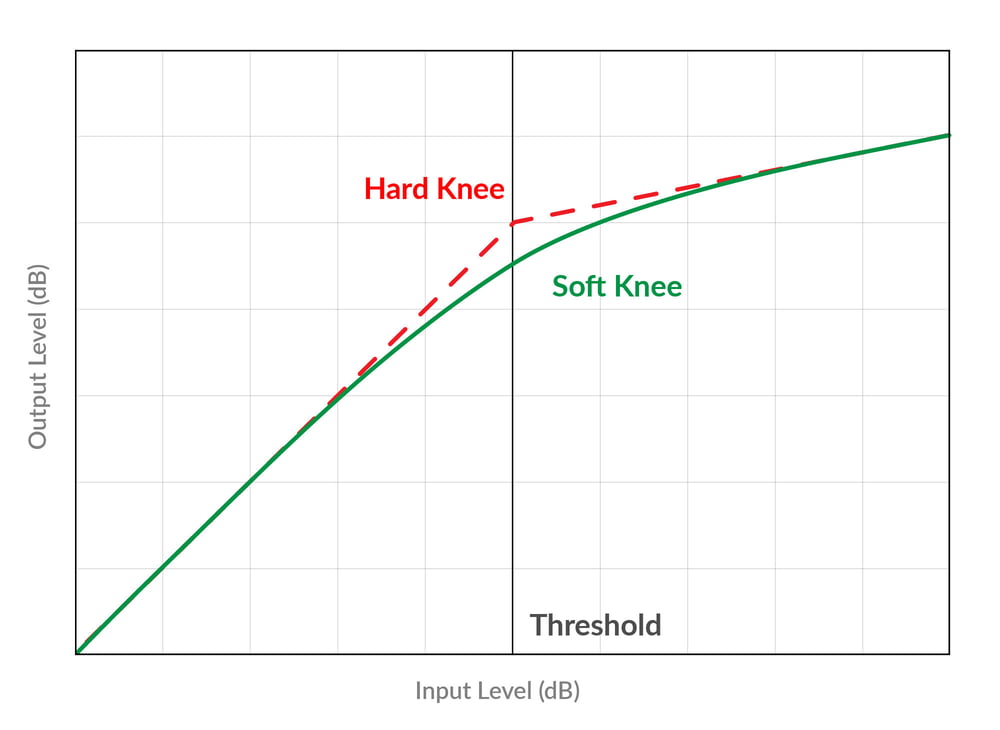

Hard knee compression works the way that compression seems to work on paper: when signal crosses the threshold, gain reduction occurs at the predetermined ratio. Below that threshold, no reduction occurs.

With soft knee compression, the ratio still determines the intensity of gain reduction, and compression still kicks in around the threshold. But instead of that reduction happening abruptly when signal crosses the line, the compressor introduces reduction more gradually — easing in from a lower ratio, starting at a point below the actual threshold.

The diagram below illustrates this concept: the hard knee curve shows a sudden change in slope (ratio) that begins at the threshold. The soft knee curve, in contrast, shows a more gradual change. Some gentle compression kicks in before the actual threshold, and it doesn’t reach its ultimate ratio destination until a bit past that threshold.

Who Kneeds to Know?

If you’re new to this stuff, and feel like this new information is just making your life needlessly complicated, here’s some good news: many compressors don’t even have a control for knee, instead featuring a more-or-less baked-in knee behavior that engineers know and rely on. If you have a favorite compressor or two, chances are you are already familiar with their knee behavior even if you weren’t aware of it.

In practice, knee helps establish how “smoothly” a compressor behaves. Do you want the effect to be subtle or overt? If you’ve ever found a compressor to be too ugly and aggressive or, conversely, not aggressive enough, there’s a solid chance that the knee was part of your problem.

Here are a few examples to help you get your head around how to get knee right.

Scenario #1: Moderate Knee Whack-a-Mole Compression

The concept of the “whack-a-mole” compressor was introduced to me by my friend and colleague Max Foreman. It’s a simple trick that can be used for effective dynamic control on just about any sound source.

The idea is to use compression in a way that is targeted at just a handful of the loudest moments on a track. The result is a little more consistency in the track in question, making it easier to make effective processing choices down the line.

A soft-knee compression curve sort of runs contrary to what this type of compression is about. We’re just trying to get the dynamic outliers, not the quieter parts. On the other hand, the goal is still to be relatively transparent, so hard knee compression might make that difficult.

For those reasons, a moderate knee setting is usually just right for this approach. The compression can be applied surgically, but with enough finesse to keep it from leaving too obvious a mark on the source material.

This type of compression is best used to dial in modest gain reduction — a couple dB at most — and is best used as a setup for other dynamic processing. It likely won’t be enough compression on its own, but can help prepare the source track for all the other processing you plan to do to it.

Scenario #2: Transparent Vocal Leveling

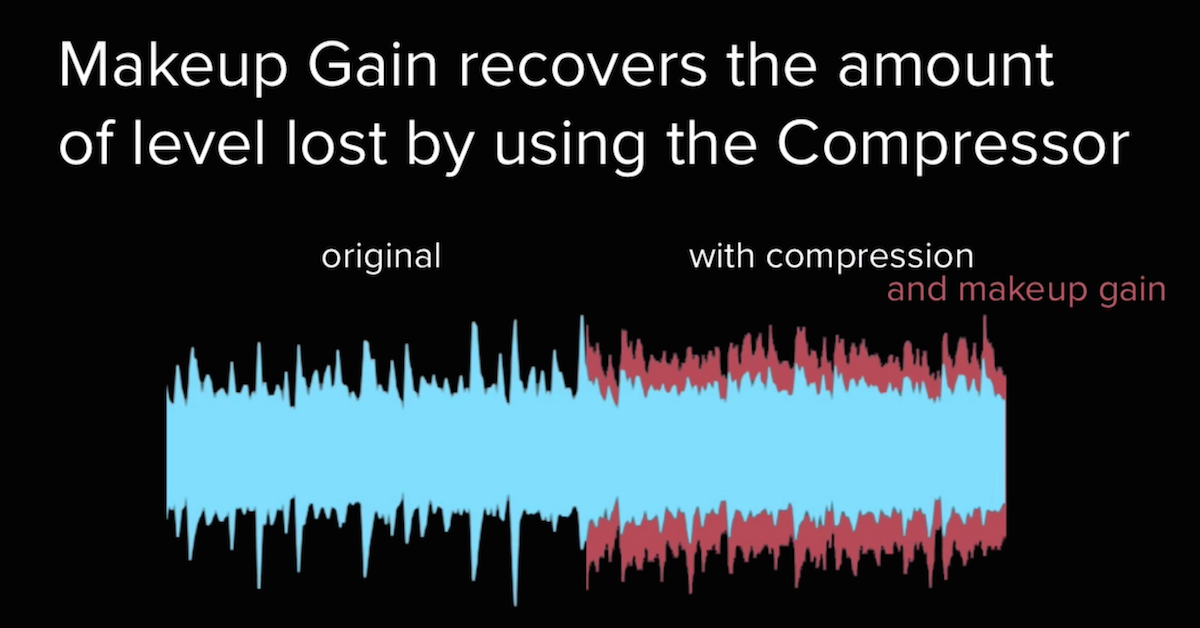

The keyword for soft knee compression is smooth, because the transition from uncompressed to fully compressed occurs in a gradual, natural way. The classic use for this type of compression is vocals, though any other legato source material might benefit as well. Think strings, woodwinds and legato synths.

One of the most popular vocal compressors — arguably the most popular — is the LA-2A. It has an inherently soft knee that is almost always just right for vocals. Even if a $4,000 hardware compressor is not in your budget, there is no shortage of great plugin emulations of the LA-2A. The Waves CLA-2A is typically on sale for $30-40.

If those LA-2A emulations are still off the table for you, you can still get some smooth and silky vocal compression with your DAW’s stock compressor. Just dial in a soft knee, moderate ratio (try 2:1 or 3:1), gentle attack & release times and set your threshold for 2-4 dB of compression.

This type of soft knee vocal compression pairs especially well with the sort of targeted dynamic control I described in my ratio article. With the right combination of smooth and surgical, it’s easy to dial in a lead vocal that confidently sits at the front of a mix.

Scenario #3: Strictly Business Hard Knee Drum Compression

Drum compression is such a broad topic, potentially referring to some pretty different applications of the same tool. In this case, I’m talking about the most basic, single channel drum compression like you’d see on a kick or snare track.

The goal of compression here is pretty clear-cut: to increase consistency, to sculpt the transient & sustain of each hit and to introduce some pleasant harmonic coloration. Hard knee compression works best in these sorts of instances — the sort of transparency that can result from softer knee compression just isn’t necessary.

The rest of the compressor’s settings are going to be dependent on your taste and the needs of the song. For extra snap, keep the attack time slow; for weight, go fast. Time the release so that it breathes with the part. Try high ratios for aggressive, modern-sounding productions, but keep the ratio low for something more vintage and subtle.

Conclusion

When we’re dialing in compression, knee can be a bit less make-or-break than, say, attack and release times. That said, it can often be the factor that determines how “musically” a compressor behaves, and for that reason it’s worth paying attention to. Next time you find yourself reaching for a compressor, just remember to ask yourself whether “smooth” is a quality you’re after. If you have a clear sense of what you’re going for, it isn’t hard to find the right knee setting for the job.