Tips for Visualizing Compression

Article Content

Compression is one of the most widely discussed topics, yet also one of the most misunderstood.

In my recent Groove 3 video tutorial series titled “Compression Explained”, the goal was to create something that isn’t just another generic compression tutorial. In order to do that, it was of the utmost importance to offer new information, to make it approachable for the absolute beginner, but also have enough technical “geekery” in there to satisfy the veteran’s appetite for more, more, more. Being an audio trainer and tech for most of my career, I fundamentally understand the importance of having both.

When first learning about dynamic range compression, it’s easy to fall into the trap of using recipes and presets. You’ll hear things like “apply 4 dB of reduction to the snare” or “use an attack time of 15ms on a vocal”. I’ll be the first to admit that when I was first learning about audio and compression, there was a certain allure to copying settings that are used to make a certain sound. It was easy, but I still felt something was missing. What most articles fail to take into consideration is the actual sound of the audio.

Breaking Through

As I grew as an engineer and a tech, and started spending more time around others in the industry, I was able to forget about all of those presets and recipes. Now I can visit any studio, grab any compressor, and dial in a sound that is just right. I can have fun with it, I can connect to the audio on a more personal level, and play with nuance. At this stage for my own skill level, it’s not about knowing what all of the buttons and knobs do, it’s more about feel. And that is certainly something that unfortunately cannot be taught, only learned.

So yeah, Dave, how do you do that?

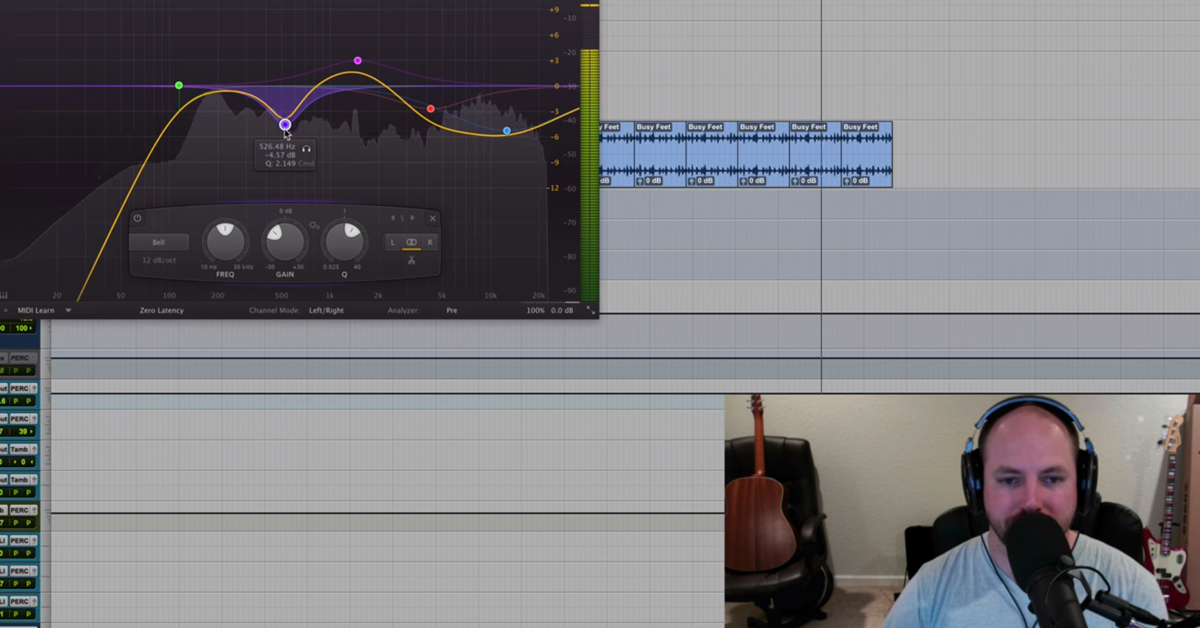

One of the biggest breakthroughs for me as an engineer was learning to visualize or “auralize” how I’m manipulating audio.

I dislike when a subject like EQ, compression, monitoring or levels is broken down and singled out, and then talked about as if it’s a process that you have to go through. We’re making music, not working in a factory. So when approaching a subject like compression that is both fundamentally easy, yet so difficult to achieve nuance, it’s most important to forget your habits and recipes and continually revisit the basics. After all, a compressor is just something that controls the volume of an audio signal. Nothing more. Learn how the compressor works on a fundamental basis, and try to relate that to what we hear. So, in the Compression Explained series, I really tried to hit home on that. I was forced to almost forget everything I knew, and revisit the basics in order to be able to teach it. It was one of the best things I could have done for myself.

Visualizing

You may hear from time to time that it’s important to close your eyes when you mix. What the eyes don’t see, the ears will hear. You enhance your feel, touch, and listening ability. With that, we start to form mental pictures of what’s going on.

When I visualize compression, I see it as pressure. Some instruments I visualize as one form of pressure, as if someone is pushing on my chest. Other instruments I visualize as a beach ball floating in the ocean. Sometimes I visualize a hammer hitting a nail, or a watermelon being thrown onto a mattress. It’s a very situational and technical thing!!

The floating beach ball analogy may best describe this. You know what happens when you try to push a beach ball under water? It tries to float to the top (fig 1). If there are waves in the water, the beach ball wants to go up and down with the waves (fig 2). Those waves are the equivalent to our incoming audio, and our output signal represents the beach ball. If we apply pressure to the beach ball to push it under water, we’re using our hand as the compressor. Think for a moment about what that feels like. Think about the feeling of pushing a ball under the water line. Feel the pressure of pushing down and the resistance of the beach ball.

The threshold is essentially how deep we want to push the ball under the water, and the ratio determines how much force we have to apply to push it to that limit of the threshold (fig 3 & fig 4). These settings go hand in hand, it’s a symbiotic relationship. You can’t have one without the other. If it’s a particularly wavy day, we’ll need to use more pressure to push the ball to that spot where our threshold lives under the water. The attack and release describe how fast we react to the changing waves.

So after years of study, do I only think about a floating beach ball? Of course not. The technical details are still very much a part of the process, but they are no longer a part of the decision. I know it may sound terribly rudimentary and almost silly, but the main point here is to understand how to revisit the basics and turn what you know, into something that you can feel.

Application

Understanding this visualization or “auralization” of pressure is one thing, but being able to apply it is something completely different. So technically speaking, what am I actually doing behind the scenes?

First, I’m massaging transients.

If you can imagine letting go of that beach ball under the water, and it flies back up to surface, that would be our transient. I try to get different transients from different instruments to poke through. I don’t think about levels too much at this point. I’m designing the transients of my mix. Sometimes it helps for me to turn my volume down and see which instrument’s transients are poking through and tickling my ears.

The next step involves manipulating what I call the “inner dynamics.”

These are the things that aren’t transients. We’re talking about the RMS, or average loudness levels. We’re talking about the knee of the attack, release, and lastly, we’re talking about the makeup gain. Inner dynamics are truly where the “feeling” comes in to the picture. Also, it’s where your technical prowess will shine after spending countless late nights on the audio community forums reading about compression and how so-and-so does it.

In my opinion, the inner dynamics are where the art of compression comes in to play. The idea is to be able to hear and feel the original dynamics of the audio without compression, then use the threshold and ratio to help it. So back to the beach ball, this would be the equivalent of holding the beach ball under water, then slightly allowing the waves to take it up and down, but not too much. This obviously has an effect on all of those transients you spent so much time designing, so it’s best to go light, and use serial compression if necessary.

Sometimes you can’t rely on compression just to accomplish this task, and that’s where fader automation comes into play. The key is to know the limits on what a compressor can and cannot do. Since unmastered reference material can be so difficult to find, many people don’t know what a finished mix is supposed to sound like. You may be surprised — a good mix can sound a bit on the unfinished side, and the levels will err on the side of caution. But, it will have plenty of room to breathe. That’s called headroom. Yet at the same time it will be dynamically balanced, and have some tasty snap from the transients. The transients will play in this area of the headroom.

Another one of the best things I could have done that helped my compression skills was monitoring at the proper levels. Maybe we’ll save that topic for another day.

The main point here is to first do your time and truly understand how a compressor works, what it does down to a circuit level, then when you are feeling empty and unrewarded from compression, forget about it all.

Realize that compression is merely a tool to control the dynamics. Next, close your eyes then feel it. Like our friend Neo in the Matrix. Don’t think you are, know you are. Be the one. Well, the compressor that is.

For more great info about compression, check out Dave’s video series at Groove3.com.