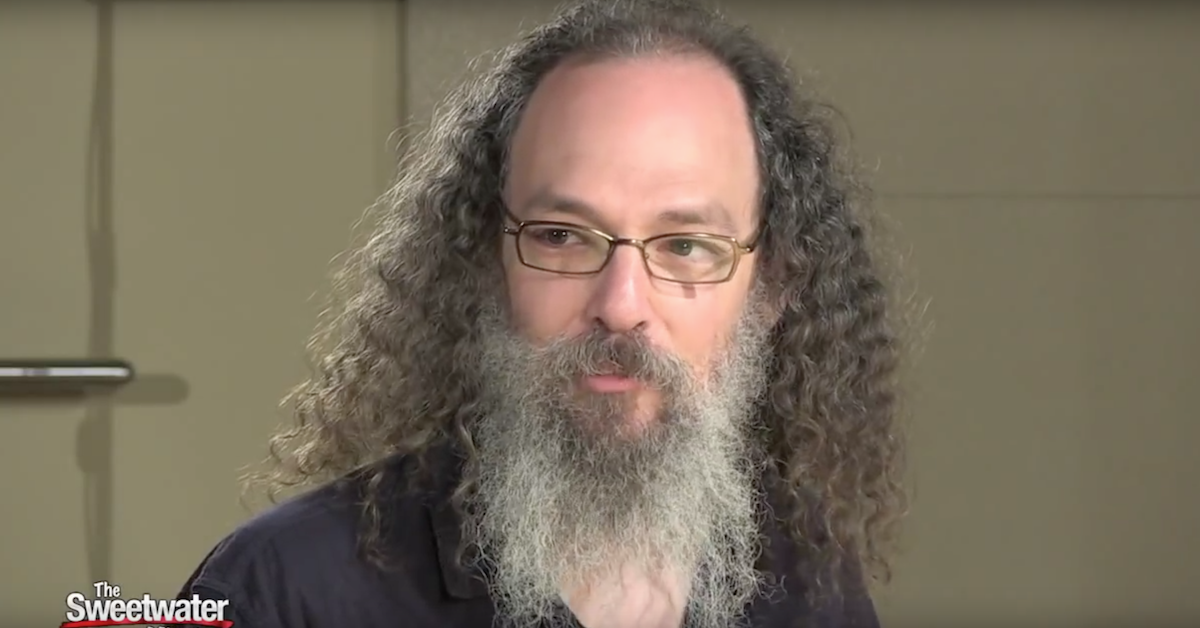

Interview with Score Mixer Phil McGowan

Article Content

I recently spoke with Phil McGowan, score mixer for numerous award-winning television shows, films and video games. His recent works include mixes for several Netflix Original Series including Ozark, The Defenders, Daredevil and Iron Fist, the video game Detroit: Become Human and upcoming films Boy Erased, Hunter Killer, Redbad and Asura. He is the owner of McGowan Soundworks, Ltd. in Los Angeles, CA.

Hi Phil, thanks for taking the time to answer these questions. Firstly, how did you become interested in music?

Both of my parents are musicians, though not professionally. My Dad plays organ & keyboards and my Mom is a classically trained pianist with a Music Education degree — so I grew up around music. When I was in the 2nd grade, I started taking piano lessons as I was jealous that my older sister was receiving lessons and I wanted in! Once I got to Junior High, I had a desire to be in the concert band so I took up Alto Sax, which became my primary instrument through college. I always loved listening to a variety of music but particularly fell in love with Jazz and Instrumental music as a kid. The first time I remember really noticing the score in a movie is when I saw Titanic for the 2nd time with my mom and sister and began to recognize music from the soundtrack album in the film. That sparked my interest in film music and eventually led me to initially desire to be a film composer.

A lot of people have a passion for music, but never become interested in the engineering and technology side of it. At what point did you develop an interest in how music was recorded and produced?

From as early as I can remember, my Dad had a few keyboards around the house that ran through a little Mackie compact mixer into a pair of Alesis studio monitors that I loved playing around with. At the time, he was also the director of the youth band at my local church and when I was 12, I tried playing keyboards in the band. My chops weren’t really there yet, which frustrated me, so my Dad suggested I hang with the sound guys since he knew I was a nerd and that I wanted to stay involved. After getting some training on the sound system for the band and learning my XLR cable from my 1/4”, I started to really enjoy learning everything I could about audio gear and had fun mixing music live. I read every gear manual I could get my hands on cover to cover and started to research everything I could about audio on the internet. This was the early 2000s so there were some resources available but nothing like the scale of great information that is out there now.

In 2004, after a few years of helping a local engineer out with some small live sound gigs, a friend of my High School Band teacher gave me his old Digidesign Audiomedia III card with a copy of Pro Tools 5 as he had just upgraded his home studio to a TDM system. That started getting me really interested in recording and studio music production and I began to record some local bands and artists as well as my high school band concerts. Within a year or so of acquiring Pro Tools, I became serious about going into music professionally and discovered Berklee College of Music’s MP&E program, where I graduated from in 2009.

Can you describe what Score Mixing typically entails on any given project?

Ideally, my job on a project starts with recording orchestra or whatever live elements will be recorded for the score, but these days, a lot of projects record overseas and nobody goes or there isn’t budget to fly me out, so I end up being hired to just mix the score. When I’m going to be recording, I have a chat with the composer about what the makeup of the orchestra is going to be and prefer to listen to any demos that they have ready to get a feel for the style of the score. Next, I’ll establish how I’m going to arrange the players in the room in addition to deciding what the mic layout will be. At this point, I’ll also try to reach out to the music & dialogue re-recording mixer to find out what format they’ll be dubbing the film in as that will determine how many ambient microphones I’ll need to put up to accommodate mixing in 5.1, 7.1 or Dolby Atmos. Once all of the recording is finished, I’ll move into the mixing phase where I’ll be blending together any recorded live elements with layers of pre-lays from the composer’s sequencer. Depending on how many channels the dub can handle, I’ll deliver anywhere from 6 to 12 or more stems for every music cue. Each stem is dedicated to a specific musical element though I’ll sometimes use stems for things they aren’t labeled for if I need to split out an element that doesn’t have a home somewhere else.

In what ways is score mixing similar to mixing music that isn’t created specifically for visual media and in what ways is it different?

Many things are very similar to mixing songs in that I’m still working with levels, panning, EQ, compression and effects. Given that scores run the gamut of genres and styles, pretty much every mixing technique that you learn from mixing songs will apply in some way to mixing a score. The main differences are that I’m typically mixing in surround, bussing everything down to stems and also have to consider how the music will fit into the bigger sonic picture of the project. Surround mixing involves a whole new set of skills and tools in addition to having to consider how the surround mix will translate down to stereo. You also have to know how to calibrate your monitoring environment as the Film and TV world have specific calibration levels that the dub adheres to so you have to be sure that the mixes you deliver work within those specs.

Given that I typically don’t have an enormous amount of time to get through many minutes of music, I don’t have time to solo and export groups of tracks as stems one by one so all of the stemming in my mix sessions is built to print in one pass once I’m finished with the mix. This means that my templates can involve some pretty complicated bussing to make everything work in one go without having reverbs for different elements crossed between stems and such. Finally, I always have to maintain a sense of how each cue will work sonically against what is going on with sound effects and dialogue. I always have rough guide tracks of dialogue and preliminary sound effects to give me a sense of what is going on in the scene so I can check my mix against these rough elements to get an idea of how things are playing together. Sometimes I have the luxury of getting 5.1 or 7.1 predubs from the sound team so I can really get a sense of what else is going on.

Are there any products, tools or technology that you couldn’t do your job without?

Not to knock on any other DAWs, but for what I do, I can’t imagine working in any software other than Pro Tools. I’ve explored the features of other DAWs and nothing else has as much flexibility in regards to bussing, grouping, session import and surround functionality.

Some of my go-to plugins that I use on almost every mix are Exponential Audio Symphony, Altiverb, FabFilter Pro-Q 2, Avid Pro Limiter and a number of UAD plug-ins. I also use Halo Upmix and Penteo quite a bit when I’m working in surround, depending on the source material. The only outboard gear that I use is a couple of Lexicon PCM96 Surround reverbs that I still really like on Strings and Brass.

What are some of the challenges you run into when working on mixing a score?

The first things that come to mind is schedule. Typically, I’m required to get through 15-20 minutes of music per day on a film and when I’m working on TV, I often only have a single day for an entire episode. Some shows only have about 20 minutes of music but I’ve had to get through 35 to almost 40 minutes of music for a single episode of TV in a day. Getting through that much material quickly requires you to be very organized and have a system of importing settings from cue to cue so you can mix quickly and not mess up stemming.

Apart from that, you still have to make sure it sounds good as well! It can be a challenge mixing a wide variety of genres in any given score. Not every film score is nice big orchestra with some other elements added, I’ve mixed scores ranging from that to purely Electronic Music, Rock, Jazz, Folk or any combination of genres you can think of.

You’ve also done a great deal of recording throughout your career. How has a background in recording helped you as a mixer?

As much as I believe that the mix is the most important stage of any production, having well-recorded material really makes a huge difference when you get to the mix. Understanding how something might have been recorded helps guide you in how to mix elements that you did not record and don’t have much info on. Conversely, having now done a great deal of mixing, when I get the luxury of being able to record as well as mix on a project, knowing how every element and microphone is going to fit into the bigger picture in the mix helps inform how many microphones I’m going to put up, what mics to use and what level to record things at. Always looking at the big picture of where things are going to end up from writing to recording to mixing to how the music is going to work in the dub keeps you from having to second guess many decisions.

How important is collaboration and working well with others in your profession?

Collaboration is everything in the entertainment industry, whether you’re working on films or on records. In the end, even though being a producer or an engineer is a very creative profession, it’s still a service job at heart. You’re being hired by an artist to help them achieve their creative vision and keeping that in mind every day is paramount to being successful in this industry.

Whether you’re an engineer, producer, session musician, orchestrator, arranger, programmer or any other supportive professional, it’s easy to get precious about things that you do but you have to always remember that it’s not your project — it’s your client’s project. As artists hire us to bring our experience, knowledge and instinct to the table, you, of course, will voice your professional opinion when you feel strongly about something but the buck still stops with the client.

What makes you most proud when working on a project?

When I finish a project that I both feel satisfied with and the client is also happy, that’s a great feeling. I’ve worked on plenty of things that I’m not in love with and on some projects, I’m just happy when they’re over. When you get to work on something that is both artistically rewarding and involves a great collaborative experience with fellow professionals, it’s much easier to feel proud of a job well done. All that being said, even if the material (either on the screen or coming through the speakers) isn’t all that inspiring, I’m almost always proud when I feel I’ve done my job well and the client is happy with my work.

Do you have any advice for young engineers who are interested in pursuing a career in audio for film, television and gaming?

As I somewhat alluded to above, one of the most important aspects of being successful in this industry is having a good attitude and demeanor. You could be an incredible producer, mixer or engineer but if your clients can’t stand to be in the room with you, your talents almost become a moot point. Of course, you have to have talent and skill in your given profession, but most clients would rather choose someone who’s a joy to work with than someone who is full of themselves and a pain, even if they have great talent.

Apart from always keeping your attitude and demeanor in mind, I would advise young people to just start absorbing as much information from people working in this field as you can. Websites like this are a fantastic resource and the more point of views you can get, the broader your knowledge will become. As you learn more and more, you eventually have to put your knowledge into practice so seek out as many opportunities to record and mix that you can. If you can manage to get some gear, offer to record and mix for local bands and artists and start cutting your teeth with whatever you can. If you decide that this is a career that you’d seriously like to pursue, there are a number of great schools out there that will teach you a lot and help you get set on a path to working in the industry. Some people are self-reliant enough to learn the essentials on their own and that’s a totally valid path to take but regardless of how you decide to start, you have to really put the effort in to learn, even if you’re at a great school.