Interview with ‘The Americans’ Composer Nathan Barr

Article Content

I was fortunate enough to have spoken with two-time Emmy-nominated Composer Nathan Barr recently about his work on the 2019 Golden Globes winner for Best TV Drama, The Americans, his recent experience scoring The House with a Clock in Its Walls and a variety of other topics.

Ian Vargo: Congrats on finishing The Americans on such a high note. From the very start, you gave Phillip and Elizabeth each their own very distinct sonic palette. What is your approach to choosing a set of sounds for characters like that?

Nathan Barr: I think there was something cold and icy about Elizabeth, so her theme was originally played on a sort of prepared piano with a hardwood mallet. I felt that the instrument had a similar kind of coldness to it. Then with Phillip, I felt like he was a tortured soul with a lot going on underneath. That low cello theme seemed to play to that nicely and spoke to his struggle of balancing his dedication to the cause and to his family. I think that Philip was more tortured than Elizabeth and these two musical settings spoke to that.

IV: In retrospect, do you have a favorite musical moment from working on The Americans?

NB: There are a lot of them. The ones that come to mind are from the first episode or two, especially when Phillips’ theme is first introduced as he goes down into the laundry room and opens the safe. It’s called “Safe Disguises” on the album. That was such a formative moment for the music as far as what his theme was going to be, and also for him as a character – this naked moment revealing who he really is.

And then I really like one of the cues that I wrote when Nina is dreaming before she’s executed. There’s a beautiful shot of her going outside after she finds out she’s been released, and then “boom” – she’s dead.

Really, there are quite a few moments that I love. An interesting thing that people may not know is that Joe and Joel actually asked me to score the last big sequence in the finale. They knew they would probably stick with the U2 song that was used, which I thought was amazing for the moment, but I said that I’d give it a try. I did write a score piece that was six or seven minutes long, which they really loved, but it confirmed to them that the moment did call for a song. In a funny way, it was my way of saying goodbye to the show. Working with that beautiful moment where Paige got off the train was so powerful. It’s a big moment that would’ve been memorable score-wise but just wasn’t meant to be.

IV: So how does it feel going from a spy/espionage thriller like The Americans to something with the grandeur and scope of The House with a Clock in Its Walls?

NB: It was such a welcome thing. I’ve done about 40 films, and I think a lot of composers can relate to having a lot of different kinds of music inside themselves waiting to be expressed. One of the difficult aspects of being a film and television composer is that we are limited to the kinds of projects we are hired on in a given year. The House with a Clock in Its Walls was the score I was waiting to write for 20 years. It was one of the easiest scores I’ve ever written and it kind of just happened. It was pure joy to be working with a big orchestra in my new studio, and to use the organ that I restored. It was the fifth collaboration between Eli Roth and me as far as director/composer and was a magical experience that was great all around.

IV: I’ve read about your desire to be involved in film from the very start — I’m sure there were some challenging moments, what kept you going?

NB: I love doing it. Even if the films don’t find a big audience, which many of the 40 films I’ve scored have not, I still absolutely love the process. Sitting down and writing music to picture absolutely feels like my calling, so that’s what keeps me going. Then, you hope to attract the attention of a really great filmmaker, which is probably the story for all film and television composers.

IV: I also read that you hope to use the Wurlitzer pipe organ in a way that doesn’t necessarily suggest a church organ, but in fact, use it a bit more like a synthesizer. How do you plan to achieve that, and how is it setup to be used that way?

NB: That organ was installed at Fox in 1928, and was pulled out in 1998. For most of its life, it was used for its ability to make a church organ sound. Even though it can generate that sound, it’s sort of the farthest thing from what it was built for. Listen to “The Mighty Wurlitzer” on The House With a Clock In Its Walls soundtrack, which is music written for the end credits. That entire piece is just for this organ. It’s the true “theatre organ” sound that this instrument was built for, so it’s a real celebration and reintroduction of that sound to contemporary film. I also used the organ to double parts played on violins, celli, and other instruments, which created a really unique sound for the score.

Literally three days ago, we got Logic hooked up to the organ, which means everything I said about wanting to use it in an unorthodox way is about to come to life. I can now actually compose for it from my sequencer. The sounds we’ve gotten out of it by letting the sequencer speak to it, as opposed to an organist, are pretty extraordinary.

IV: So are you sending MIDI notes from Logic to it?

NB: Exactly. We’re sending MIDI notes from Logic to the rudimentary computer system that was built for this instrument. Then, that computer is taking the MIDI and translating it to its own language, before it then goes to speak to all the pipes and other musical elements in the organ. Once it leaves that secondary computer, it is functioning exactly as it did in 1928 – with only magnets, wind and electricity.

IV: Wow, MIDI-capable pianos, that technology has been around for some time, but to have an organ like that to be able to receive MIDI …

NB: Yeah, it’s very cool. The system that was installed in-between the console (keyboards) and the pipes wasn’t designed for me. A man named Dick Wilcox developed that system maybe 40 years ago, and the really wonderful thing about it is that any organist that sits down at the keyboards can hit “record”, and anything they play is basically captured by a MIDI-like language. Then the organ will spit it back out exactly as they played it – like a giant player piano.

IV: The possibilities are limitless.

NB: Yeah, absolutely. Up until a couple days ago, not being a player got in the way of composing for it. I could sit down and multitrack in real time by playing it all, but now I can actually sit in my writing room, sequence on many independent ranks of the organ, and build super complex parts that are well beyond the capabilities of a single player. It’s all very exciting territory.

IV: On past projects, about 75% of the music is you performing and layering parts, in that situation are you handling the recording duties as well?

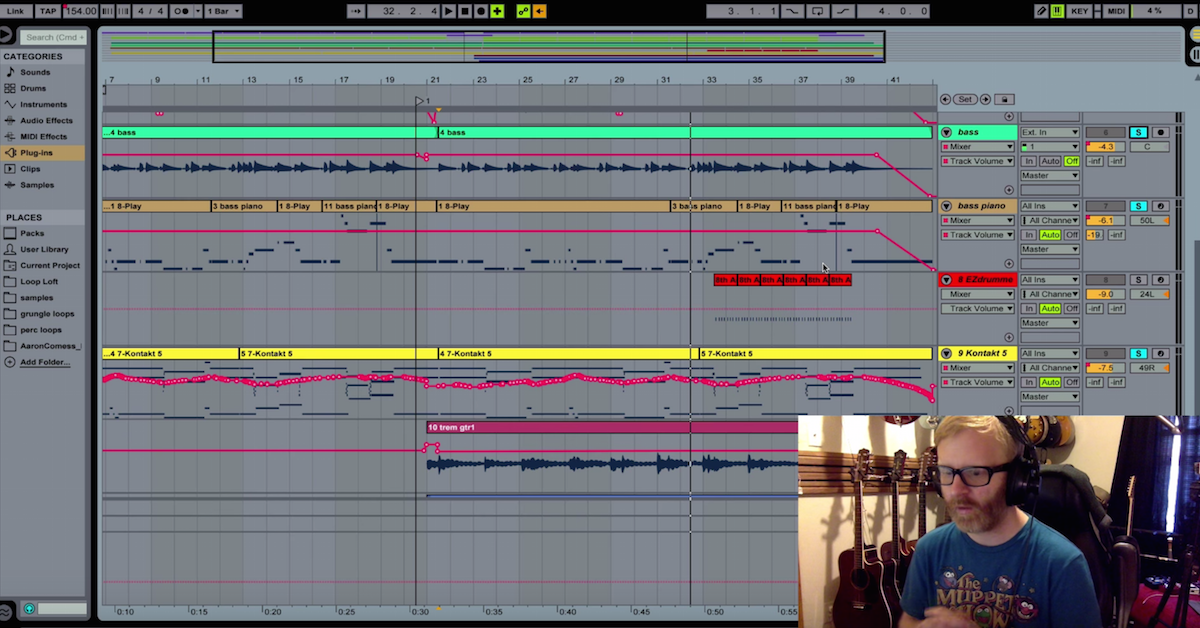

NB: Yes, I now have assistants who engineer for me, but a show like The Americans was all about live recording. Maybe even 80-90% of that score is always live stuff. In my new studio, I have a large scoring stage with all kinds of instruments set up around it, and I move from station to station while someone works Pro Tools or Logic, and we record the parts. When I’m done playing the parts, the cues are basically done. When I started out doing this about 15 years ago, it took longer to turn cues around because there was a performance element that had to be perfect. As I’ve gotten better and more comfortable now, it’s like killing two birds with one stone. You get something that’s really organic, alive and breathing.

IV: You’re well-known for using mostly live instruments in your scores, are there any virtual instruments that you’ve been enjoying lately?

NB: Yeah, definitely. I’m doing this new show called The Rook on Starz, and we’ve been using a lot of Omnisphere and Zebra patches. That is certainly all great stuff. I really like Output, who make these Rev Loops which are very useful. Arcade is one of their loop synths which I did a video for, which is also very useful. We composers are often very under the gun, and when companies like Output or Spitfire come up with these cool pads that you can use as inspiration to compose over the top of, it can be a real time-saver in a crunch.

IV: What types of projects do you hope to do at Bandrika in the near future?

NB: I hope to continue along the lines of the bigger scope film work, like The House with a Clock in Its Walls. I’d like to attract at least a couple of directors whose work I respect to come and see the studio and understand that I’m thinking about things a bit differently from standard film & TV music, and then work on their projects. TV-wise, kind of the same thing. We also do concerts here, and we’re having a really amazing organist named Richard Hills come over from the UK on February 9. It’s just a beautiful space that helps me celebrate the importance of keeping live music around. The Bridge, another recording studio on a similar scale as this one, just closed within the past year and that is very sad. All these studios in Los Angeles are shuttering, leaving this incredible pool of musicians who are completely willing and wanting to work more than they are. I’m hoping that live recording will stay alive in this town because it’s filled with some of the world’s greatest musicians.