An Introduction to Ambient Music (+ 12 Favorite Plugins)

Article Content

It’s safe to say that throughout most of musical history, the way a note sounded (timbre) was less considered, less controllable and less important to the music producers of the past than it is today. Granted, those musicians who came before us still had plenty of other musical parameters to think about, such as the selection of pitches and how to combine them with others into harmonies and melodies, all while developing rhythmic and formal designs. Of course they didn’t have the incredible sound shaping tools we have today either. Consider this context as we continue on from here.

Since being labeled by Brian Eno as ambient music in the mid 1970s, this underground and nebulous genre has tantalized many listeners with its heightened focus on the timbral musical element and with some experimental approaches to composition. Creators of this music usually rely heavily on the electronic tools and production techniques traditionally found in recording studios during the entire production process, including during composition. This approach can be incredibly rewarding to explore in the box, where we have easy access to precision timbre shaping tools like virtual instruments, DAW automation and robust digital signal processing. These tools provide a potent playground for sound design. This focus on timbre also makes ambient music a fruitful area of study for audio engineers. An ear that’s well tuned to subtle shifts in timbre and dynamics is a prerequisite for success in the field, after all. Many of the tools and techniques used to (often) subtle effect in ambient music can be easily transferred to other genres, regardless if they end up being used subtly or not. The music, according to Eno, can be “as ignorable as it is interesting;” I find it to be intoxicating and mesmerizing when it’s at its best, though new listeners will need to be prepared to abandon the often deep-seated expectation of hearing certain common compositional approaches in this music, such as harmonic progressions, standardized forms and thematic development.

In this article, I’ll be taking a look at one of the most influential of these experimental composition techniques and suggesting how you can experiment with that technique in your productions. Then I’ll be offering a brief historical overview of the genre’s development, sharing a couple of production tips and presenting my picks for the 12 best plugins to use when producing ambient music in the box.

Generative Techniques

Those previously mentioned experimental and electronics-focused approaches to composition led to the development of a collection of new and fascinating composition techniques and production strategies, including some that take advantage of generative music technologies. Based on the idea that a music maker can deploy some sort of randomized, semi-randomized or indeterminate musical element(s) in the production process, the results of musical designs executed through generative techniques are rarely the same from one playback to the next. Of course this field of composition owes much to the legendary New York avant-garde composer John Cage and his ideas on indeterminacy. I find generative techniques to offer a revolutionary way to think about creating a hybrid live/recorded musical experience.

Given that randomization is an important element in its production, generative music is usually produced and consumed via computers nowadays due to a computer’s ability to easily make random selections, but this wasn’t always the case. In Terry Riley’s famous 1964 composition for any type of ensemble titled In C, for example, the indeterminate element was achieved by establishing a sequence of 53 simple musical modules that each performer repeats as many times as they like, within certain constraints. The moment of advancement to the next module in the sequence is left up to each individual in the ensemble, and is executed independently from other performers. This simple idea produces an incredible amount of variety with each performance. Still, each unique performance is recognizable as In C due to the pre-planned pitches, rhythms and sequencing of the individual modules. But how the performer-to-performer interaction across the ensemble will unfold is unpredictable and provides something new and enjoyable to discover with every new performance.

Production Tip #1:

There’s a fun and relatively simple generative tool in Ableton Live that can be used to produce generative music. With follow actions, Live can be instructed to select from a group of prepared clips randomly during playback, and user-specified probabilities can be deployed to inform this process. With a bit of study, thought and effort, this simple feature can turn Ableton Live’s session view into an ever-evolving generative playground. There are other generative tools in Live too, including MIDI note and velocity generators, and randomized LFO shapes that can be mapped to nearly any parameter. Each of these tools are capable of constraining random values to within user specified ranges.

To illustrate how this might play out, take a look at this screenshot from Live’s “session view.”

Live’s session view was a major development in DAW technology. The session view presents individual tracks as vertical rows, as opposed to the horizontal rows found in nearly all other DAWs (and in Live too, where the environment containing horizontal tracks is referred to as the “arrangement view”). Within each vertical track, a number of clip slots allow for the preparation and spontaneous playback of a number of different musical ideas, with each track being capable of playing back one clip at a time. In the image above, taken from a generative Ableton Live set of mine titled Music for Nina, each vertical track contains a particular MIDI-driven virtual instrument or a set of audio recordings. Each rectangular clip that appears on the grid contains a pre-composed idea, but as the generative process plays out, which particular clip in each vertical track ends up being the one that’s actively playing at any given moment is left up to a certain degree of chance.

We can hear the process in action by comparing two separate documentations (recordings) of the generative process playing out:

Listen for the Rhodes piano loop. It’s the first sound heard in both recordings, and is the only part to remain constantly sounding throughout. It’s a repetitive loop that’s one 12/8 bar in length at a BPM of 40. Within this group of four Rhodes loops pictured on the track farthest left, two are predominantly in C major and two are predominantly in A minor. I was able to assign a probability that there would be a 98% chance that the currently playing loop would repeat upon completion, while 2% of the time a randomly selected other loop from the track would play instead. Each and every other clip in the session view undergoes the same process, though the particulars of the probabilities vary from clip to clip.

(Example 1: C major to A minor at 5:32, a randomly selected moment)

(Example 2: C major to A minor at 2:24, a randomly selected moment)

Ambient Music’s Beginnings

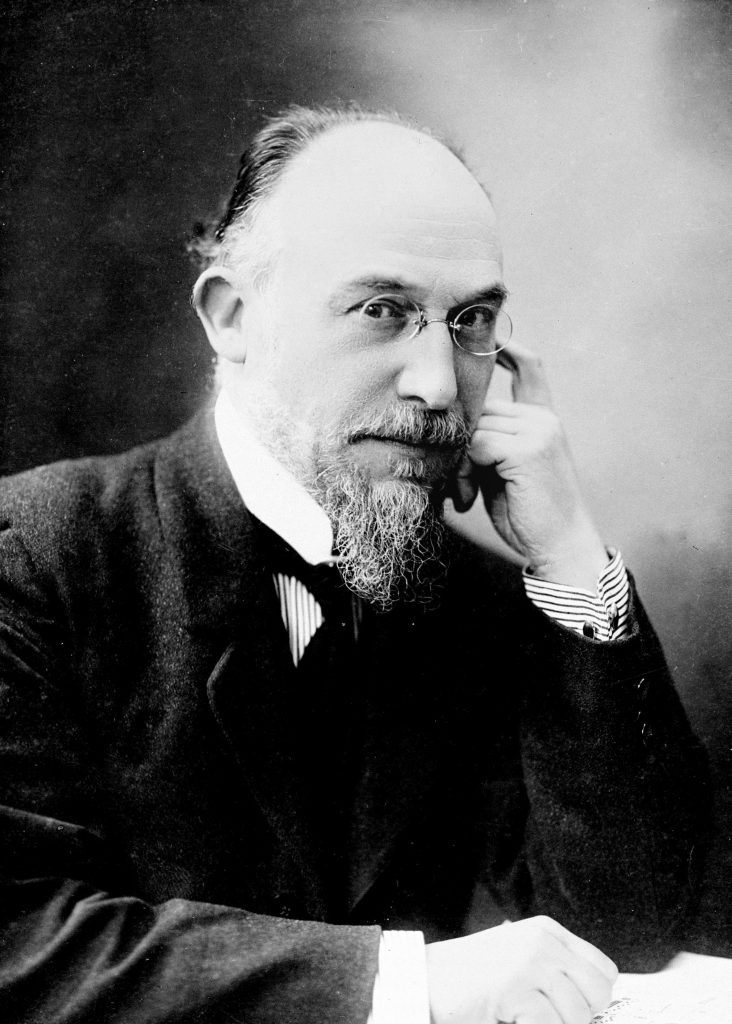

Some may argue (I would be among them) that the true beginnings of both ambient and minimalist music can be traced back to the eccentric and profoundly innovative French composer Erik Satie (1866-1925). There was a pretty important early contribution to impressionist music there too, which Claude Debussy (a friend of Satie’s) would go on to masterfully develop — signaling the beginning of the modern age in music. Satie is a musician that is mainly known for the piano music he wrote between 1887-1897, including the Sarabandes, Gymnopedies, and Gnossiennes. John Cage, who played a major role in reviving Satie’s music during a time when it was in danger of becoming forgotten, said of Satie: “It’s not a question of Satie’s relevance. He’s indispensable.” I agree, and I think that Satie’s ideas continue to wield a substantial influence on musical culture.

Getting back to the ambient connection, in 1917 Satie wrote what he described as “furniture music.” This is perhaps where the most direct conceptual comparison to modern day ambient music can be made. With furniture music, the function or purpose of the music shifted away from being the usual center of attention (like in a concert scenario) to being intended to blend into the background (ambience) of the surrounding environment. Of course today background music is ubiquitous, but at the time this idea was most certainly out of the ordinary. Satie’s music has had a lasting influence on some of the most important composers who came after, like John Cage, Philip Glass and Richard D. James (AKA Aphex Twin), whose 2001 album Drukqs contains (among other things) a collection of piano pieces that bear a bit more than a passing resemblance to some of Satie’s best known music. These piano pieces also sometimes make use of piano preparations, a timbre altering technique largely developed by John Cage.

The next major figure in the development of ambient music would have to be Brian Eno. Take a look at his 1979 essay titled “The Studio as a Compositional Tool” for insight as to why this is; I consider it to be a visionary and classic document from the era. In the essay, Eno considers the ramifications of writing music through a process of intensive listening and sonic discovery that could only happen through experimenting with studio-based technologies. In 1975 Eno’s work in the genre as a solo artist began with Discreet Music, however it was Eno’s 1973 tape loop collaboration with Robert Fripp titled No Pussyfooting where I think we can first begin to hear the post-Satie ambient genre starting to form.

Eno’s work was a tremendous revival and reimagining of ambient music. His early ambient albums were often formed through a fascinating approach to “systems” music (closely related to generative music), where the composer would design a set of rules and techniques that would govern (by one degree or another) the note to note details of a composition. In Eno’s classic 1978 album Ambient 1: Music for Airports, the system takes the form of a series of tape loops, each of a different length. These tapes were strung all over the studio, but once they were set up all would be played back through a mixer and blended together there. With the loops being of different lengths, each time a loop ended and then began again it would have a different timing relationship to the others, creating an unpredictable sequence of musical events as this process played out. Eno did a lot of wonderful sound design work on the early ambient albums too, with Discreet Music being one of the especially important synthesizer recordings of the 1970s and Ambient 1: Music for Airports establishing a number of acoustic timbres that would become the sonic bedrock of the genre for generations.

If you’re thinking about producing some ambient music in the box, I’ve prepared a list of 12 excellent plugins (plus a few honorable mentions) for this purpose. I’ve divided them into six virtual instruments and six processors.

Top 6 Virtual Instruments (1-6)

Good sound design starts at the instrument level. This is the portion of the software receiving MIDI data and outputting audio that can be fed into digital signal processing devices such as delay, reverb, EQ, compression and saturation (see entries 7-12).

Virtual instruments are at their best when they provide the user with a powerful set of sound shaping tools while being intuitive to use and quick to operate. With instruments based on sample libraries, an element of realism may be desired as well. These things are, of course, not easy to achieve.

1. The Giant by Native Instruments

When you need the literal sound of an enormous piano, accept no other virtual substitutes. Pianos have been an important source of sonic material in the genre ever since Satie’s famous piano works and Eno’s Ambient 1/Music for Airports. Sampled from the Klavins Piano Model 370i, this two ton, ten foot piano is so large that it’s built into the wall of the building that houses it. I tend to think of pianos as having a “standard” (think Steinway Model D) sound or a “character” (think barroom piano) sound. This instrument can be placed squarely in the latter category.

Honorable mention: Hammersmith Pro by Soniccouture. A meticulously sampled Steinway Model D, this Kontakt instrument delivers a whopping 6 mic positions and 21 velocity layers. Make sure you’ve got plenty of RAM available; this is a 52 GB (!) instrument.

2. Native Instruments/SCARBEE MARK I

The Rhodes pianos are still making sounds that are beloved even now, over 70 years after they were first introduced. It’s no surprise, they just sound great: mellow and sweet, with a pleasing note envelope being produced by the instrument’s unique tines. The recording techniques used in producing this sample library resulted in a nice, warm, pliable and playable Rhodes sound.

Honorable mention: Ableton’s Suitcase Piano. Part of the Electric Keyboards pack.

Included with the Ableton Suite edition, those with access to this excellent sampled instrument probably won’t need to go looking for an upgrade anytime soon.

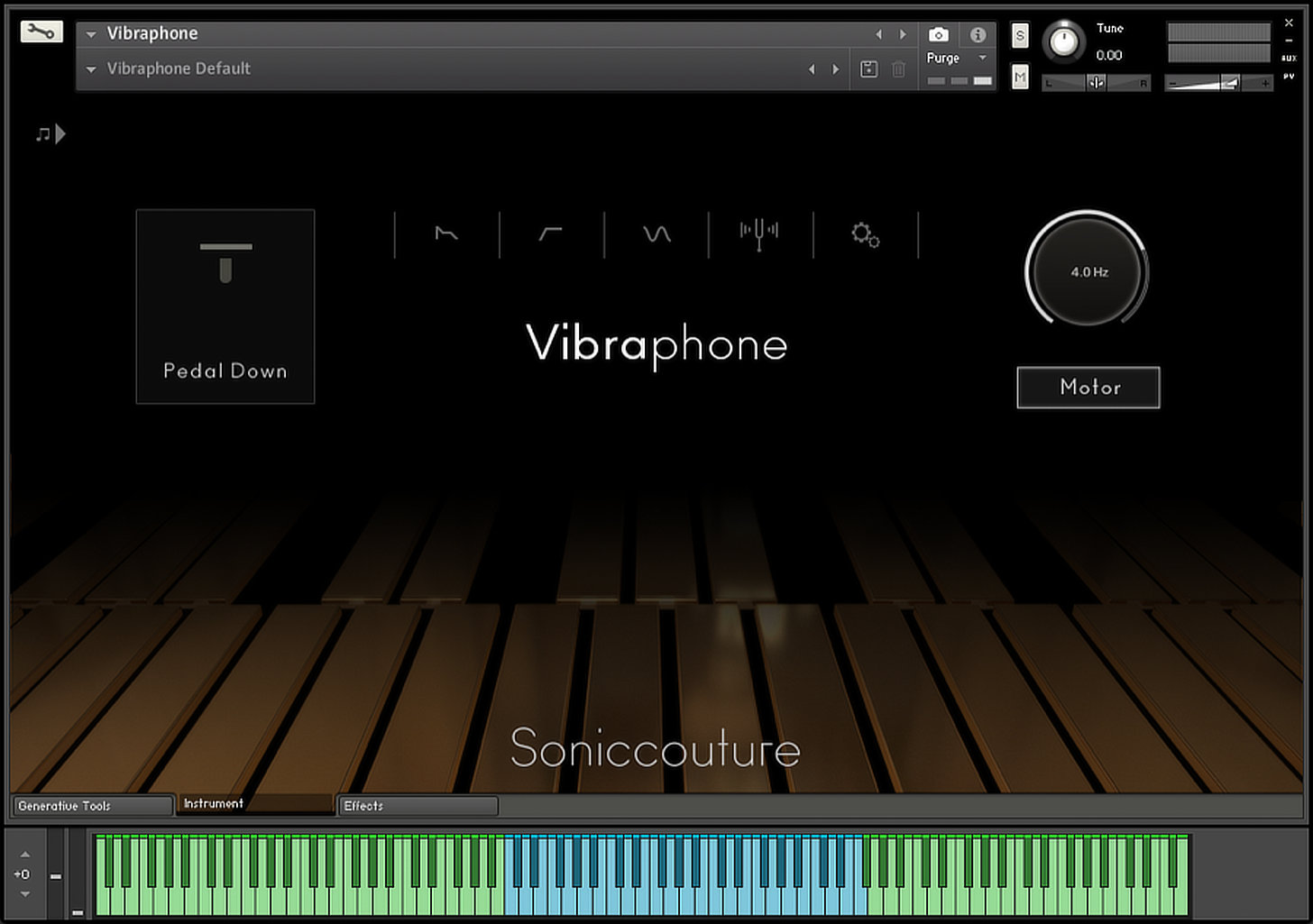

3. Vibraphone by Soniccouture

The vibraphone is capable of producing anything from a mild, inviting sustained timbre when struck softly, to a bright, aggressive and thoroughly metallic sound when struck aggressively. This sample library covers it all, and includes a flexible and terrific sounding motor-based vibrato. The only major vibraphone playing technique not covered here is a bowed sound, but Fracture Sounds has that well-covered at a reasonable price with their Frozen Vibes instrument.

4. Diva by u-he

Diva is the absolute holy grail in analog synthesizer emulation. In addition to its outstanding sound quality, this instrument also features a powerful design where modeled modules from certain unnamed (but relatively obvious) classic synthesizer models can be patched into modules from others. So if you want to hear what it would sound like if you fed a Jupiter 6 oscillator into a Minimoog ladder filter, well, you may just be able to get a good idea of what that would sound like here.

Honorable mention: Phonec by Psychic Modulation.

While this isn’t the most flexible virtual analog synth on the market, it might do the best job at simulating all of the little idiosyncrasies that give true analog synthesis its character.

5. Zebra 2 by u-he

A modern synthesizer capable of a wide range of synthesis types and timbral-shaping tools is an incredibly valuable tool for an ambient producer seeking new sonic ground, and this is exactly what u-he’s Zebra 2 offers. U-he refers to Zebra 2 as their “workhorse synth,” and that’s an appropriate label for this remarkable instrument. It’s an instrument that has achieved a remarkable feat: it’s wildly successful in its ability to balance flexibility, precision, power, excellent sound quality and ease of use.

Zebra 2 is modular in its architecture, with some limitations. Some modular systems don’t place limits on the number of modules that can be deployed in a patch; u-he has opted instead to provide a fixed number of slots in which the included modules can be freely loaded. I’ve been especially impressed with the oscillators offered here. Traditional analog, wavetable and FM techniques are covered, plus there’s an interesting and useful option for spectral processing right inside the oscillator. The modulation system is both simple and powerful, offering flexible multi-segment envelopes, plenty of LFOs with modern capabilities and the usual MIDI-based modulation options. Making connections between modulators and modulation destinations is easy and can be accomplished right at the destination parameter or in the provided modulation matrix. Then there’s a wide-ranging collection of great-sounding filters and effects provided for timbre shaping and adding that final polish to a patch. Zebra 2 may not be the right choice for every single synthesis situation, but it’s going to be able to achieve what you’re after in an astonishingly high number of situations.

6. Wavetable by Ableton

Here’s Ableton’s second virtual instrument that’s a genuine instant classic, the first being the highly regarded Operator, of course. The additional oscillator-level modulation capabilities offered by wavetable synthesis truly opens up new sound design horizons, and this instrument delivers on that promise with flexible oscillators supporting custom designed wavetables, rich and characterful filters, easy to use modulation, flexible signal routing and more. Best of all, I’ve never found an instrument so easy to learn, intuitive to use and light on CPU.

Honorable Mention: Pigments by Arturia.

This is a real powerhouse instrument. In addition to a very capable wavetable engine, this instrument also includes virtual analog, sample playback and sample based granular synthesis modes. This instrument reminds me a lot of Alchemy, created long ago by Camel Audio and now owned by Apple, but Pigments is far more user friendly and you can use it outside of Logic.

Top 6 Effects Processors (7-12)

But first, Production tip #2:

Use generous amounts of reverb and delay. Use them often. Seriously, slather it on. Use them well. Of course, this recommendation is depends very much on the particular context of your production, but this is a genre where the effects you use can be responsible for the bulk of your sound, rather than acting as a mere enhancement to another sound. Ambient producer Forrest Fang, who releases ambient music on the Projekt label, had this to say on the topic of reverb plugins: “Uh oh. Another sale on reverb plugins. For ambient musicians like myself, this is the equivalent of happy hour.”

Reverbs and Delays can be addicting. The varied plugins on the market offer the sound designer an exceptionally robust sonic palette. Here are three of my favorites, plus a compressor and a modulator to round things out.

7. The Entire Valhalla DSP Lineup

Yes, this is cheating. Ok, if I had to pick one I’d go with the gorgeous and absolutely stunning-sounding Shimmer, but this is purely based on my own personal taste.

What’s not to love about the Valhalla DSP plugins? Each and every one of these algorithmic plugins has a deep, polished sound, and each one is sonically unique. Considering the always reasonable price tag, these plugins are, in my opinion, essential. Try out the three outstanding free plugins to get a taste of what this company’s processing tools can do.

8. IR-1 by Waves

Convolution reverbs like the IR-1 are an essential addition to the reverb toolbox. These plugins excel at creating realistic sounding spaces due to their particular approach to generating the reverb. There are a lot of excellent convolution reverbs on the market, but this entry from Waves has a huge library of impulse responses, sounds great and can be had for a good price (if you can be patient with the constant on sale then not on sale pricing from Waves).

9. Little Plate by Soundtoys

This instantly became my go-to plate reverb upon its release. The plugin has a smooth and refined sound that’s easy to fit into the mix, and the user interface could not be more simple to operate. Instant plate atmosphere.

10. Supercharger GT by Native Instruments

This is a hidden gem of a plugin. It’s both a capable compressor and a flexible saturator in one package. It’s phenomenal for sprucing up bland sounds with a bit of mellow flavor or a good amount of distortion. When I use saturation I almost always place it directly after the compressor in the signal chain anyway, so in addition to sounding good, this plugin adds convenience into the mix.

11. Shaperbox 2 by Cableguys

This plugin contains a suite of incredibly flexible and capable modulation tools. At the heart of every Cableguys plugin is the powerful ability to create user designed LFO shapes, and they can be as simple or complex as you want. These shapes can then drive just about any parameter on the included effects: pan, volume, width, drive, filter, bitcrusher, and time. A mind boggling array of highly customizable effects can be generated over time in this plugin.

12. Twangstrom by u-he

Spring reverbs have a very specific sound that’s immediately identifiable, and as such these types of reverbs are generally appropriate for only a limited range of applications — at least in comparison to the more widely applied room, hall and plate reverbs. u-he’s Twangstrom, though, offers an unusually wide range of possibilities for a plugin focused on spring sounds. This starts with the three different spring tanks that have been modeled. One option offers two springs and the other two offer three. These virtual springs can have their tensions adjusted at will by the user — there’s even a readout that’ll tell you the spring’s pitch at any given tension. Very cool.

Typical of u-he’s offerings, the sound quality is outstanding and just about any parameter can be modulated — there’s an envelope and an LFO built-in. Also included are filter and drive modules. This is an impressive spring reverb; it’s my new go-to plugin for when I’m thinking about adding a spring sound to my productions.

Conclusion

There’s no time like the present to dive in and start getting to know this genre. The historically important music mentioned above is a good place to start, but there are other giants of the genre that might capture your interest, including Aphex Twin, Stars of the Lid, William Basinski, Laurie Spiegel, and more. Go ahead and get inside the sound.