What is a Program-Dependent Compressor?

Article Content

Dynamic range compressors are an essential tool for a mixing engineer. In almost all styles of music, compressors are an effect used on most instruments in every mix.

Relatively speaking, compressors behave in a pretty complicated way. On one hand, this behavior makes it possible to do all kinds of things to a mix like smooth, excite, glue, shape, punch, duck, and bite. One the other hand, this complicated behavior makes a compressor somewhat of a mystery to understand.

In particular, one complicated aspect of a compressor is program-dependence. Let’s take a look at: What is it? How does it work? Why would you want to use it?

Before going any further, it is worth pointing out that not all compressors have program-dependent behavior. In fact, most standard digital compressors are not program-dependent. Instead, this behavior is more commonly found in analog compressors and in specific digital models of analog compressors. As some examples, the LA-2A, LA-3A, 1176, Fairchild, Distressor, and many dbx compressors are program-dependent. Whether or not a digital emulation of an LA-2A is program-dependent is based on the particular software plugin you use. Some have it and some don’t. Some of the plugins that try to model it, do it accurately and others don’t.

Furthermore, when engineers say, “there are just some things about analog compressors that are lacking in digital compressors,” this usually means one of two things. First, analog circuits can exhibit subtle non-linear saturation. Second, and more relevant here, is the program-dependence.

What Is Program-Dependence?

The name program-dependence comes from the fact that a compressor’s behavior can change based on (i.e. depends on) the input signal (historically called program material). Theoretically, there are many different parameters that could change in a compressor based on an input signal (threshold, ratio), but in almost all cases it is the attack and release times that change.

Now you might be thinking, “there must be some sophisticated circuit doing a meticulous analysis of all the possible signals sent through a compressor to determine the attack and release times!” In reality, it is typically a single circuit component that is responsible for, and inherently causes, program-dependence. This component is a photoresistor. In the LA-2A, a well-known type of photoresistor is used called the T4 Cell. The unique, irregular behavior of this component controls the response time of the compressor.

As a side note, there are differing stories about whether program-dependence was an intentional characteristic of early analog compressors or whether it was an unintended side-effect. Regardless of whether it was a “bug” or a “feature,” we should all appreciate that it was discovered. Nowadays, many coveted vintage compressors are the ones with a T4 Cell from a particular era.

How Does It Work?

For comparison purposes, a standard digital compressor typically has parameters to set the attack and release time in milliseconds. The good and bad thing about digital effects is that they can be very precise. When you set a release time of 100 ms, you can be certain it will be 100 ms. Program-dependence is essentially the exact opposite of this. For some input signals, the response time is fast and other signals it is slow.

Here is a description of how the response time generally works with an LA-2A:

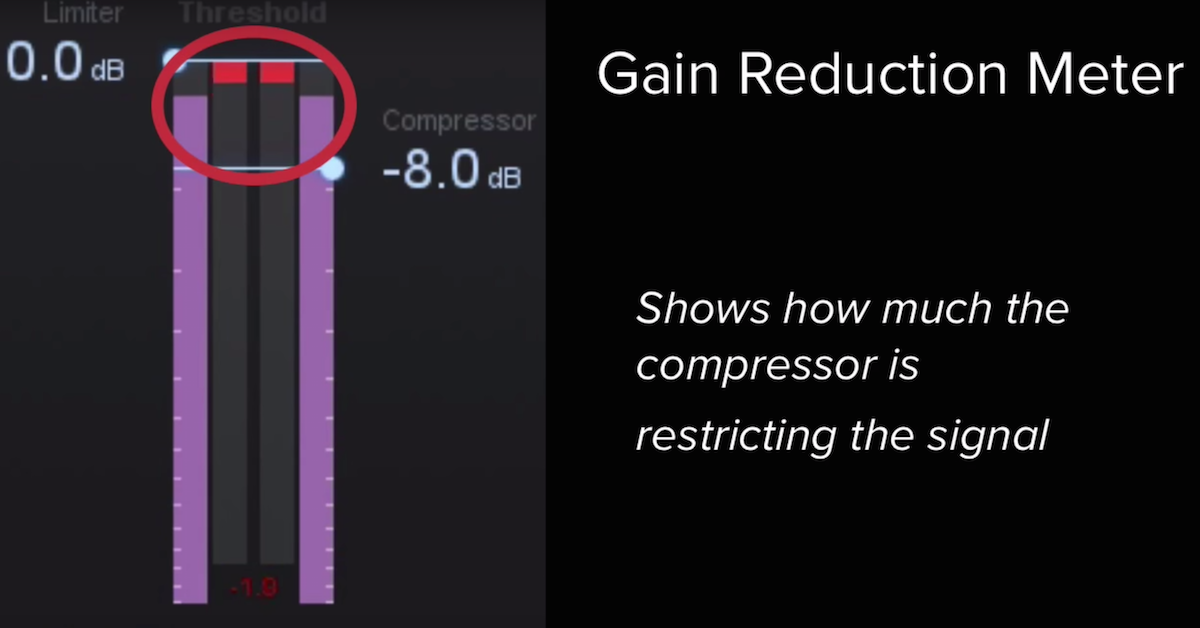

Suppose the compressor has settled out to a state with 0 dB of gain reduction. If an input signal comes in that would cause the gain reduction to increase by a small amount to 1 dB GR, the attack time will be very slow to smoothly bring in that gain reduction. However, if an input signal comes in with a transient that causes the gain reduction to increase by a large amount to 10 dB GR, the attack time will be much faster to grab on quickly to the input signal.

Here is the coolest part of the program-dependence. Suppose you are compressing a vocal and already have roughly 6 dB of gain reduction, if the input signal causes the GR to go up or down by 1 dB, the response time will be very slow because only a small amount of new GR is actually changing. This is precisely what causes a program-dependent compressor to sound so smooth, even when high amounts of gain reduction are applied. A basic digital compressor definitely won’t do that.

The release time of an LA-2A generally behaves in a similar and complementary way. When the gain reduction starts at 1 dB and needs to decrease down to 0 dB, the release time will be very slow (possibly even 5 to 10+ seconds). When the input signal is causing 10 dB of gain reduction and then all of a sudden drops out, the gain reduction will quickly decrease with a fast release time and then gradually slow down as the GR gets to a point of transitioning from 1 dB to 0 dB. This is described many times as a “two-stage release” in the LA-2A. However, there aren’t actually two entirely distinct stages with different release times that change abruptly. From actual measurements of the hardware, it can be seen that the release actually transitions in a much more gradual way from fast to slow.

Why Should You Want to Use It?

So in closing, why does any of this matter to you as a mix engineer? Although program-dependent compressors may have been an accident in their original invention, it could be argued that this general behavior is actually ideal for many signals compared to having the attack and release be fixed.

Program-dependence is one important characteristic for giving a compressor a “sound.” It is one legitimate reason some engineers prefer analog compressors to digital, and why some digital models of compressors are better than others. But I’m not going to point out any particular versions here.

Many of the famous recordings we all love were created using program-dependent compressors. We are familiar with how program-dependence sounds, and it sounds very musical because the compressor responds to how the input signal changes.

Lastly, program-dependent compressors can make mixing easier and faster. You could spend an endless amount of time trying to get the exact right attack and release time. Or you could try out a couple of different options of program-dependent compressors, crank up the gain reduction, and you will probably get better results anyway.