3 Techniques for Mixing Background Vocals

Article Content

Background vocals aren’t just “more singing”; they have a job in the arrangement.

Specifically, background vocals are usually either:

- A layer of the lead vocal intended to provide strength through tonal complexity.

- An additional instrumental idea intended to provide harmonic context for the melody.

Whether you’re planning overdubs or you’re in the middle of a mix, it’s never too late to be sure the background vocals are fulfilling their musical ‘special purpose’.

Here are a few simple techniques that help:

1. Mono Layers

When a vocal track is intended to be a layer of the lead vocal track (like a double or simple parallel harmony), the layered effect is more easily achieved without stereo separation.

Unfortunately the tonal complexity and dynamic range of a lot of vocal performances can make mono vocal layers inconsistent or just plain confusing.

To help establish the lead vocal track as the primary vocal track try:

- Limiting the bandwidth of the background vocal track(s) with high-pass filtering (you could go as high as 200Hz without affecting lyrical intelligibility)

- Limiting the articulation dynamics of the background vocal track(s) with de-essing (even if they aren’t too sibilant)

Simple as it sounds, the thing to remember when working on layered elements is to listen ‘in place’. The sound of an effective layer may strike you as downright nasty in isolation. Don’t make choices about the background layers unless you’re hearing their effect on the lead vocal track.

2. Power Through Symmetry

When vocal tracks are intended to provide harmonic context for the melody (like a string section or keyboard pad might), the effect is much more easily achieved with symmetrical stereo separation.

The goal with this type of background vocal technique is to create a stereo instrument that is clearly distinguished from the centered lead vocal content. If you’re still in arrangement and overdub mode, this can be easily facilitated by getting good doubles of any background vocal tracks that might be used this way.

If this goal doesn’t emerge until mixing, you’re not out of luck. A simple reflection can often be just as useful as a well-performed double. Try a static 80-110ms slap-back delay panned left to provide symmetry for the right-panned background vocal elements. Be sure to vary the delay time for the complementary right-panned delay by at least 10%.

If this technique introduces too much depth (perception of distance), a much shorter delay time (20-40ms) can be used. Just be sure to introduce a little slow modulation to these shorter delays to avoid unpleasant static phase problems.

3. Group Processing

Whether your goal is a mono layer of lead vocal content or a supporting stereo vocal instrument, the objective is to get a group of individual audio tracks to behave as a single instrument. Group processing is a simple and effective way to achieve this.

For example, one big difference between the sound of a beautiful stereo vocal pad and ‘just a bunch of vocal tracks’ can be shared dynamics. A stereo-linked compressor across a background vocal subgroup will help create both dynamic and tonal homogeny within the group. Processing the constituent tracks individually can’t provide the same affect.

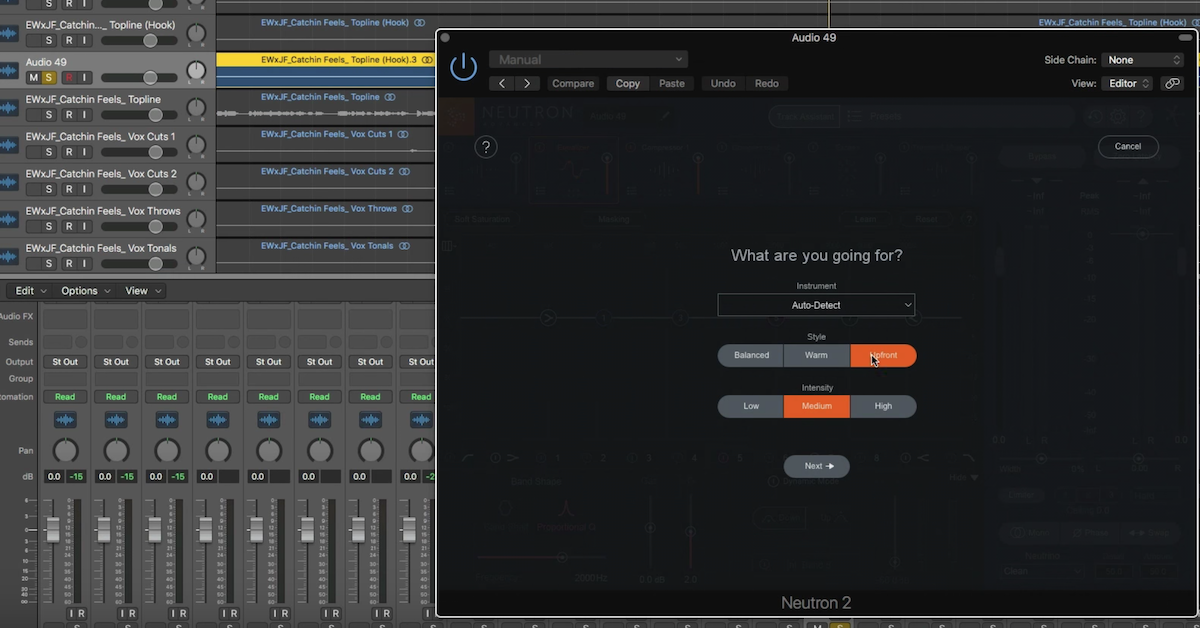

Similarly, a mono vocal layer (like a Hip-Hop lead and its doubles) often needs attention in the midrange to make sure it has a focused place in the track. Doing that EQ work in a subgroup can help strengthen the perception that these individual tracks are a single, tonally complex, musically powerful instrument.

Start with a Plan

It’s never too early in the process to begin considering these ideas. A well-produced overdub session has a way of taking hours off of the mixing process.

Of course these techniques can apply just as well to other types of tracks like guitars, horn sections, and keyboard layers. Each application might have its own idiosyncrasies, but the concepts are the same.